TAANACH (Jos 12:21, 1 K 4:12, 1 Ch 7:29).—One of the royal Canaanite cities, mentioned in OT always along with Megiddo. Though in the territory of Issachar, it belonged to Manasseh; the native Canaanites were, however, not driven out (Jos 17:11–13, Jg 1:27) . It was allotted to the Levites of the children of Kohath (Jos 21:25). It was one of the four fortress cities on the ‘border of Manasseh’ (1 Ch 7:29). The fight of Deborah and Barak with the Canaanites is described (Jg 5:19) as ‘in Taanach by the waters of Megiddo.” The site is to-day Tell Ta‘annak, four miles S.E. from Tell el-Mutesellim ( Megiddo). The hill has been excavated by Prof. Sellin of Vienna. Many remains of Canaanite and Jewish civilization have been found, and also a considerable number of clay tablets with cuneiform inscriptions similar to those discovered at Tell el-Amarna in Egypt. See Sellin in Mem. Vienna Acad., 1. (1904), lii. (1905).

E. W. G. MASTERMAN.

TAANATH-SHILOH.—A town on the N.E. boundary of Ephraim (Jos 16:6). It is possibly the mod. Ta‘na, about 7 miles from Nāblus (Neapolis), and 2 miles N. of Yānūn ( Janoah ).

TABAOTH (1 Es 5:29 (60); and TABBAOTH (Ezr 2:43 = Neh 7:46).—A family of Nethinim who returned with Zerubbabel.

TABBATH.—An unknown locality mentioned in Jg 7:22.

TABEEL.—1. The father of the rival to Ahaz put forward by Rezin (wh. see) and Pekah (Is 7:6). 2. A Persian official (Ezr 4:7); called in 1 Es 2:16 Tabellius.

TABELLIUS.—See TABEEL, 2.

TABER.—Only in Nah 2:7 ‘her handmaids mourn as with the voice of doves, tabering ( Amer. RV ‘beating’) upon their breasts.’ Beating the breast was a familiar Oriental custom in mourning (cf. Is 32:12). The word here used means lit. ‘drumming’ (cf. Ps 68:26, its only other occurrence). The English word ‘taber’ means a small drum, usually accompanying a pipe, both instruments being played by the same performer. Other forms are ‘tabor,’ ‘tabour,’ and ‘tambour’; and dim. forms are ‘tabret’ and ‘tambourine.’

TABERAH.—An unidentified ‘station’ of the Israelites (Nu 11:3, Dt 9:22).

TABERNACLE.—1. By ‘the tabernacle’ without further qualification, as by the more expressive designation ‘tabernacle of the congregation’ (RV more correctly ‘tent of meeting,’ see below), is usually understood the elaborate portable sanctuary which Moses erected at Sinai, in accordance with Divine instructions, as the place of worship for the Hebrew tribes during and after the wilderness wanderings. But modern criticism has revealed the fact that this artistic and costly structure is confined to the Priestly sources of the Pentateuch, and is to be carefully distinguished from a much simpler tent bearing the same name and likewise associated with Moses. The relative historicity of the two ‘tents of meeting’ will be more fully examined at the close of this article (§ 9).

2. The sections of the Priests’ Code (P) devoted to the details of the fabric and furniture of the Tabernacle, and to the arrangements for its transport from station to station in the wilderness, fall into two groups, viz. (a) Ex 25–27, 30, 31, which are couched in the form of instructions from J″ to Moses as to the erection of the Tabernacle and the making of its furniture according to the ‘pattern’ or model shown to the latter on the holy mount (25:9, 40); (b) Ex 35–40 , which tell inter alia of the carrying out of these instructions. Some additional details, particularly as to the arrangements on the march, are given in Nu 3:25ff., 4:4ff. and 7:1ff..

In these and other OT passages the wilderness sanctuary is denoted by at least a dozen different designations (see the list in Hastings’ DB iv. 655). The most frequently employed is that also borne, as we have seen, by the sacred tent of the Elohistic source (E), ‘the tent of meeting’ (so RV throughout). That this is the more correct rendering of the original ’ōhel mō‘ēd, as compared with AV’s ‘tabernacle of the congregation,’ is now universally acknowledged. The sense in which the Priestly writers, at least, understood the second term is evident from such passages as Ex 25:22, where, with reference to the mercy-seat (see 7 (b)), J″ is represented as saying: ‘there I will meet with thee and commune with thee’ (cf. Nu 7:89). This, however, does not exclude a possible early connexion of the name with that of the Babylonian ‘mount of meeting’ (Is 14:13, EV ‘congregation’), the mō‘ēd or assembly of the gods.

3. In order to do justice to the Priestly writers in their attempts to give literary shape to their ideas of Divine worship, it must be remembered that they were following in the footsteps of Ezekiel (chs. 40–48), whose conception of a sanctuary is that of a dwelling-place of the Deity ( see Ezk 37:27). Now the attribute of Israel’s God, which for these theologians of the Exile overshadowed all others, was His ineffable and almost unapproachable holiness, and the problem for Ezekiel and his priestly successors was how man in his creaturely weakness and sinfulness could with safety approach a perfectly holy God. The solution is found in the restored Temple in the one case (Ezk 40 ff.), and in the Tabernacle in the other, together with the elaborate sacrificial and propitiatory system of which each is the centre. In the Tabernacle, in particular, we have an ideal of a Divine sanctuary, every detail of which is intended to symbolize the unity, majesty, and above all the holiness of J″, and to provide an earthly habitation in which a holy God may again dwell in the midst of a holy people. ‘Let them make me a sanctuary, that I may dwell among them’ (Ex 25:8).

4. Taking this general idea of the Tabernacle with us, and leaving a fuller discussion of its religious significance and symbolism to a later section (§ 8) , let us proceed to study the arrangement and component parts of P’s ideal sanctuary. Since the tents of the Hebrew tribes, those of the priests and Levites, and the three divisions of the sanctuary—court, holy place, and the holy of holies—represent ascending degrees of holiness in the scheme of the Priestly writer, the appropriate order of study will be from without inwards, from the perimeter of the sanctuary to its centre.

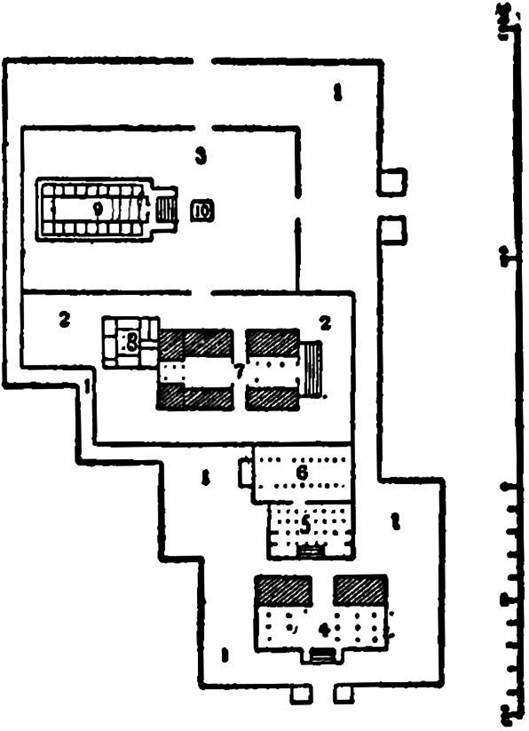

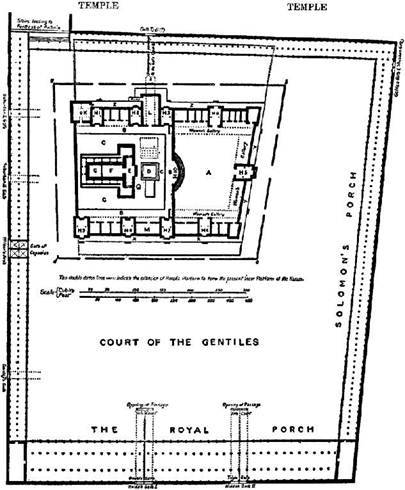

(a) We begin, therefore, with ‘the court of the dwelling’ (Ex 27:9). This is described as a rectangular enclosure in the centre of the camp, measuring 100 cubits from east to west and half that amount from south to north. If the shorter cubit of, say, 18 inches (for convenience of reckoning) be taken as the unit of measurement, this represents an area of approximately 50 yards by 25, a ratio of 2:1. The entrance, which is on the eastern side, is closed by a screen (27:16 RV) of embroidered work in colours. The rest of the area is screened off by plain white curtains (EV ‘hangings’) of ‘fine twined linen’ 5 cubits in height, suspended, like the screen, at equal intervals of 5 cubits from pillars standing in sockets (EV) or bases of bronze. Since the perimeter of the court measured 300 cubits, 60 pillars in all were required for the curtains and the screen, and are reckoned in the text in groups of tens and twenties, 20 for each long side, and 10 for each short side. The pillars are evidently intended to be kept upright by means of cords or stays fastened to pins or pegs of bronze stuck in the ground.

(b) In the centre of the court is placed the altar of burnt-offering (27:1–8), called also ‘the brazen altar’ and ‘the altar’ par excellence. When one considers the purpose it was intended to serve, one is surprised to find this altar of burnt-offering consisting of a hollow chest of acacia wood (so RV throughout, for AV ‘shittim’)—the only wood employed in the construction of the Tabernacle—5 cubits in length and breadth, and 3 in height, overlaid with what must, for reasons of transport, have been a comparatively thin sheathing of bronze. From the four corners spring the four horns of the altar, ‘of one piece’ with it, while half-way up the side there was fitted a projecting ledge, from which depended a network or grating (AV ‘grate’) of bronze (27:5, 38:4 RV). The meshes of the latter must have been sufficiently wide to permit of the sacrificial blood being dashed against the sides and base of the altar (cf. the sketch in Hastings’ DB iv. 658). Like most of the other articles of the Tabernacle furniture, the altar was provided with rings and poles for convenience of transport.

(c) In proximity to the altar must be placed the bronze laver (30:17–21), containing water for the ablutions of the priests. According to 38:8, it was made from the ‘mirrors of the women which served at the door of the tent of meeting’ (RV)—a curious anachronism.

5. (a) It has already been emphasized that the dominant conception of the Tabernacle in these chapters is that of a portable sanctuary, which is to serve as the earthly dwelling-place of the heavenly King. In harmony therewith we find the essential part of the fabric of the Tabernacle, to which every other structural detail is subsidiary, described at the outset by the characteristic designation ‘dwelling.’ ‘Thou shalt make the dwelling (EV ‘tabernacle’) of ten curtains’ (26:1). It is a fundamental mistake to regard the wooden part of the Tabernacle as of the essence of the structure, and to begin the study of the whole therefrom, as is still being done.

The ten curtains of the dwelling (mishkān) , each 28 cubits by 4, are to be of the finest linen, adorned with inwoven tapestry figures of cherubim in violet, purple, and scarlet (see COLOURS). ‘the work of the cunning workman’ (26:1ff. RV). They are to be sewed together to form two sets of five, which again are to be ‘coupled together’ by means of clasps (RV; AV ‘taches’) and loops, so as to form one large surface 40 (10×4) cubits by 28 (7×4), ‘for the dwelling shall be one’ (26:8). Together the curtains are designed to form the earthly, and, with the aid of the attendant cherubim, to symbolize the heavenly, dwelling-place of the God of Israel.

(b) The next section of the Divine directions (26:7–14) provides for the thorough protection of these delicate artistic curtains by means of three separate coverings. The first consists of eleven curtains of goats’ hair ‘for a tent over the dwelling,’ and therefore of somewhat larger dimensions than the curtains of the latter, namely 30 cubits by 4, covering, when joined together, a surface of 44 cubits by 30. The two remaining coverings are to be made respectively of rams’ skins dyed red and of the skins of a Red Sea mammal, which is probably the dugong (v. 14, RV ‘sealskins,’ Heb. tachash).

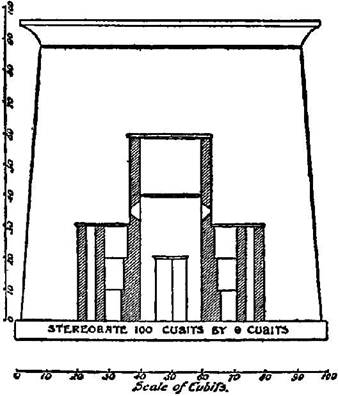

(c) At this point one would have expected to hear of the provision of a number of poles and stays by means of which the dwelling might be pitched like an ordinary tent. But the author of Ex 26:1–14 does not apply the term ‘tent’ to the curtains of the dwelling, but, as we have seen, to those of the goats’ hair covering, and instead of poles and stays we find a different and altogether unexpected arrangement in vv. 15–30. Unfortunately the crucial passage, vv. 15–17 , contains several obscure technical terms, with regard to which, in the present writer’s opinion, the true exegetical tradition has been lost. The explanation usually given, which finds in the word rendered ‘boards’ huge wooden beams of impossible dimensions, has been shown in a former study to be exegetically and intrinsically inadmissible; see art. ‘Tabernacle’ in Hastings’ DB, vol. iv. p. 563b ff. To § 7 (b) of that article, with which Haupt’s note on 1 K 7:28 in SBOT should now be compared, the student is referred for the grounds on which the following translation of the leading passage is based. ‘And thou shalt make the frames for the dwelling of acacia wood, two uprights for each frame joined together by cross rails.’ The result is, briefly, the substitution of 48 light open frames (see diagrams, op. cit.), each 10 cubits in height by 11/2 in width, for the traditional wooden beams of these dimensions, each, according to the usual theory, 1 cubit thick, equivalent to a weight of from 15 to 20 hundredweights!

The open frames—after being overlaid with gold according to our present but scarcely original text (v. 29)—are to be ‘reared up,’ side by side, along the south, west, and north sides of a rectangular enclosure measuring 30 cubits by 10 (3:1), the east side or front being left open. Twenty frames go to form each long side of the enclosure (11/2x20 = 30 cubits); the western end requires only six frames (11/2x6 = 9 cubs.); the remaining cubit of the total width is made up by the thickness of the frames and bars of the two long sides. The two remaining frames are placed at the two western corners, where, so far as can be gathered from the obscure text of v. 24, the framework is doubled for greater security. The lower ends of the two uprights of each frame are inserted into solid silver bases, which thus form a continuous foundation and give steadiness to the structure. This end is further attained by an arrangement of bars which together form three parallel sets running along all three sides, binding the whole framework together and giving it the necessary rigidity.

Over this rigid framework, and across the intervening space, are laid the tapestry curtains to form the dwelling, the symbolic figures of the cherubim now fully displayed on the sides as well as on the roof. Above these come the first of the protective coverings above described, the goats’ hair curtains of the ‘tent,’ as distinguished from the ‘dwelling.’ In virtue of their greater size, they overlap the curtains of the latter, their breadth of 30 cubits exactly sufficing for the height and width of the dwelling (10 + 10 + 10 cubits). As they thus reached to the base of the two long sides of the Tabernacle, they were probably fastened by pegs to the ground. At the eastern end the outermost curtain was probably folded in two so as to hang down for the space of two cubits over the entrance (26:9). In what manner the two remaining coverings are to be laid is not specified.

[This solution of the difficulties connected with the construction of the Tabernacle, first offered in DB iv., has been adopted, since the above was written, by the two latest commentators on Exodus, M‘Neile and Bennett; see esp. the former’s Book of Exodus [1908], lxxiii–xcii.]

(d) The fabric of the Tabernacle, as described up to this point in Ex 26:1–30 , has been found to consist of three parts, carefully distinguished from each other. These are (1) the artistic linen curtains of the dwelling, the really essential part; (2) their supporting framework, the two together enclosing, except at the still open eastern front, a space 30 cubits long and 10 cubits wide from curtain to curtain, and 10 cubits in height; and (3) the protecting tent (so called) of goats’ hair, with the two subsidiary coverings.

The next step is to provide for the division of the dwelling into two parts, in the proportion of 2 to 1, by means of a beautiful portiere, termed the veil (vv. 31ff.), of the same material and artistic workmanship as the curtains of the dwelling. The veil is to be suspended from four gilded pillars, 20 cubits from the entrance and 10 from the western end of the structure. The larger of the two divisions of the dwelling is named the holy place, the smaller the holy of holies or most holy place. From the measurements given above, it will be seen that the most holy place—the true presence-chamber of the Most High, to which the holy place forms the antechamber—has the form of a perfect cube, 10 cubits (about 15 ft.) in length, breadth, and height, enclosed on all four sides and on the roof by the curtains and their cherubim.

(e) No provision has yet been made for closing the entrance to the Tabernacle. This is now done (v. 36f.) by means of a hanging, embroidered in colours—a less artistic fabric than the tapestry of the ‘cunning workman’—measuring 10 cubits by 10, and suspended from five pillars with bases of bronze. Its special designation, ‘a screen for the door of the Tent’ (v. 36 RV), its inferior workmanship, and its bronze bases, all show that strangely enough it is not to be reckoned as a part of the dwelling, of which the woven fabric is tapestry, and the only metals silver and gold.

6. Coming now to the furniture of the dwelling, and proceeding as before from without inwards, we find the holy place provided with three articles of furniture: (a) the table of shewbread, or, more precisely, presence-bread (25:23–30, 37:10–16); (b) the so-called golden candlestick, in reality a seven-branched lampstand (25:31–40, 37:17–24) (c) the altar of incense (30:1–7, 37:25–28). Many of the details of the construction and ornamentation of these are obscure, and reference is here made, once for all, to the fuller discussion of these difficulties in the article already cited (DB iv. 662 ff.).

(a) The table of shewbread, or presence-table (Nu 4:7), is a low table or wooden stand overlaid with pure gold, 11/2 cubits in height. Its top measures 2 cubits by 1. The legs are connected by a narrow binding-rail, one hand-breadth wide, the ‘border’ of Ex 25:25, to which are attached four golden rings to receive the staves by which the table is to be carried on the march. For the service of the table are provided ‘the dishes, the spoons, the flagons, and the bowls thereof to pour withal’ (25:29 RV), all of pure gold. Of these the golden ‘dishes’ are the salvers on which the loaves of the presence-bread (see SHEWBREAD) were displayed; the ‘spoons’ are rather cups for frankincense (Lv 24:7); the flagons’ (AV ‘covers’) are the larger, and the ‘bowls’ the smaller, vessels for the wine connected with this part of the ritual.

(b) The golden candlestick or lampstand is to be constructed of ‘beaten work’ (repoussé) of pure gold. Three pairs of arms branched off at different heights from the central shaft, and curved outwards and upwards until their extremities were on a level with the top of the shaft, the whole providing stands for seven golden lamps. Shaft and arms were alike adorned with ornamentation suggested by the flower of the almond tree (cf. diagram in DB iv. 663). The golden lampstand stood on the south side of the holy place, facing the table of shewbread on the north side. The ‘tongs’ of 25:38 are really ‘snuffers’ (so AV 37:23) for dressing the wicks of the lamps, the burnt portions being placed in the ‘snuff dishes.’ Both sets of articles were of gold.

(c) The passage containing the directions for the altar of incense (Ex 30:1–7) forms part of a section (chs. 30, 31) which, there is reason to believe is a later addition to the original contents of the Priests’ Code. The altar is described as square in section, one cubit each way, and two cubits in height, with projecting horns. Like the rest of the furniture, it was made of acacia wood overlaid with gold, with the usual provision of rings and staves. Its place is in front of the veil separating the holy from the most holy place. Incense of sweet spices is to be offered upon it night and morning (30:7ff.).

7. In the most holy place are placed two distinct yet connected sacred objects, the ark and the propitiatory or mercy-seat (25:10–22, 37:1–9). (a) P’s characteristic name for the former is the ark of the testimony. The latter term is a synonym in P for the Decalogue (25:16), which was written on ‘the tables of testimony’ (31:18), deposited, according to an early tradition, within the ark. The ark itself occasionally receives the simple title of ‘the testimony,’ whence the Tabernacle as sheltering the ark is named in P both ‘the dwelling (EV ‘tabernacle’) of the testimony’ (Ex 38:21 etc.) and ‘the tent of the testimony’ (Nu 9:15 etc.). The ark of the Priests’

Code is an oblong chest of acacia wood, 21/2 cubits in length and 11/2 in breadth and height (5×3×3 half-cubits), overlaid within and without with pure gold. The sides are decorated with an obscure form of ornamentation, the ‘crown’ of Ex 25:11, probably a moulding (RVm ‘rim or moulding’). At the four corners (v. 12 AV; RV, less accurately, ‘feet’) the usual rings were attached to receive the bearing-poles. The precise point of attachment is uncertain, whether at the ends of the two long sides or of the two short sides. Since it would be more seemly that the throne of J″, presently to be described, should face in the direction of the march, it is more probable that the poles were meant to pass through rings attached to the short sides, but whether these were to be attached at the lowest point of the sides, or higher up, cannot be determined. That the Decalogue or ‘testimony’ was to find a place in the ark (25:16) has already been stated.

(b) Distinct from the ark, but resting upon and of the same superficial dimensions as its top, viz. 21/2 by 11/2 cubits, we find a slab of solid gold to which is given the name kappōreth. The best English rendering is the propitiatory (vv. 17ff.), of which the current mercy-seat, adopted by Tindale from Luther’s rendering, is a not inappropriate paraphrase. From opposite ends of the propitiatory, and ‘of one piece’ with it (v. 19 RV), rose a pair of cherubim figures of beaten work of pure gold. The faces of the cherubim were bent downwards in the direction of the propitiatory, while the wings with which each was furnished met overhead, so as to cover the propitiatory (vv. 18–20).

We have now penetrated to the Innermost shrine of the priestly sanctuary. Its very position is significant. The surrounding court is made up of two squares, 50 cubits each way, placed side by side (see above). The eastern square, with its central altar, is the worshippers’ place of meeting. The entrance to the Tabernacle proper lies along the edge of the western square, the exact centre of which is occupied by the most holy place. In the centre of the latter, again, at the point of intersection of the diagonals of the square, we may be sure, is the place intended for the ark and the propitiatory. Here in the very centre of the camp is the earthly throne of J″. Here, ‘from above the propitiatory, from between the cherubim,’ the most holy of all earth’s holy places, will God henceforth meet and commune with His servant Moses (25:22). But with Moses only; for even the high priest is permitted to enter the most holy place but once a year, on the great Day of Atonement, when he comes to sprinkle the blood of the national sin-offering ‘with his finger upon the mercy-seat’ (Lv 16:14) . The ordinary priests came only into the holy place, the lay worshipper only into ‘the court of the dwelling.’ In the course of the foregoing exposition, it will have been seen how these ascending degrees of sanctity are reflected in the materials employed in the construction of the court, holy place, most holy place, and propitiatory respectively. It is not without significance that the last named is the only article of solid gold in the whole sanctuary.

8. These observations lead naturally to a brief exposition of the religious symbolism which so evidently pervades every part of the wilderness sanctuary. Its position in the centre of the camp of the Hebrew tribes has already been more than once referred to. By this the Priestly writer would emphasize the central place which the rightly ordered worship of Israel’s covenant God must occupy in the theocratic community of the future.

The most assured fruit of the discipline of the Babylonian Exile was the final triumph of monotheism. This triumph we find reflected in the presuppositions of the Priests’ Code. One God, one sanctuary, is the idea implicit throughout. But not only is there no God but Jahweh; Jahweh, Israel’s God, ‘is one’ (Dt 6:4 RVm), and because He is one, His earthly ‘dwelling’ must be one (Ex 26:6 RV, cf. § 5 (a)) . The Tabernacle thus symbolizes both the oneness and the unity of J″.

Nor is the perpetual striving after proportion and symmetry which characterizes all the measurements of the Tabernacle and its furniture without a deeper significance. By this means the author undoubtedly seeks to symbolize the perfection and harmony of the Divine character. Thus, to take but a single illustration, the perfect cube of the most holy place, of which ‘the length and breadth and height,’ like those of the New Jerusalem of the Apocalypse (21:16), ‘are equal,’ is clearly intended to symbolize the perfection of the Divine character, the harmony and equipoise of the Divine attributes.

Above all, however, the Tabernacle in its relation to the camp embodies and symbolizes the almost unapproachable holiness of God. This fundamental conception has been repeatedly emphasized in the foregoing sections, and need be re-stated in this connexion only for the sake of completeness. The symbolism of the Tabernacle is a subject in which pious imaginations in the past have run riot, but with regard to which one must endeavour to be faithful to the ideas in the mind of the Priestly author. The threefold division of the sanctuary, for example, into court, holy place, and holy of holies, may have originally symbolized the earth, heaven, and the heaven of heavens, but for the author of Ex 25 ff. it was an essential part of the Temple tradition (cf. TEMPLE, § 7). In this case, therefore, the division should rather be taken, as in § 7 above, as a reflexion of the three grades of the theocratic community, people, priests, and high priest.

9. Reluctantly, but unavoidably, we must return, in conclusion, to the question mooted in § 2 as to the relation of the gorgeous sanctuary above described to the simple ‘tent of meeting’ of the older Pentateuch sources. In other words, is P’s Tabernacle historical? In the first place, there is no reason to question, but on the contrary every reason to accept, the data of the Elohistic source (E) regarding the Mosaic ‘tent of meeting.’ This earlier ‘tabernacle’ is first met with in Ex 33:7–11 ; ‘Now Moses used to take the tent and to pitch it [the tenses are frequentative] without the camp, afar off from the camp … and it came to pass that every one which sought the LORD went out unto the tent of meeting which was without the camp.’ To it, we are further Informed, Moses was wont to retire to commune with J″, who descended in the pillar of the cloud to talk with Moses at the door of the tent ‘as a man talketh with his friend’ (see also the references in Nu 11:16–30 , 12:1ff., 14:10). Only a mind strangely insensible to the laws of evidence, or still in the fetters of an antiquated doctrine of inspiration, could reconcile the picture of this simple tent, ‘afar off from the camp,’ with Joshua as its single non-Levitical attendant (33:11), with that of the Tabernacle of the Priests’ Code, situated in the centre of the camp, with its attendant army of priests and Levites. Moreover, neither tent nor Tabernacle is rightly intelligible except as the resting-place of the ark, the symbol of J″’s presence with His people. Now, the oldest of our extant historical sources have much to tell us of the fortunes of the ark from the time that it formed the glory of the Temple at Shiloh until it entered its final resting-place in that of Solomon

(see ARK) . But nowhere is there the slightest reference to anything in the least resembling the Tabernacle of §§ 4–8. It is only in the Books of Chronicles, in certain of the Psalms, and in passages of the pre-exilic writings which have passed through the hands of late post-exilic editors that such references are found. An illuminating example occurs in 2 Ch 1:3f. compared with 1 K 3:2ff..

Apart, therefore, from the numerous difficulties presented by the description of the Tabernacle and its furniture, such as the strangely inappropriate brazen altar (§ 4 (b)) , or suggested by the unexpected wealth of material and artistic skill necessary for its construction, modern students of the Pentateuch find the picture of the desert sanctuary and its worship irreconcilable with the historical development of religion and the cultus in Israel. In Ex 25 and following chapters we are dealing not with historical fact, but with ‘the product of religious idealism’; and surely these devout idealists of the Exile should command our admiration as they deserve our gratitude. If the Tabernacle is an ideal, it is truly an ideal worthy of Him for whose worship it seeks to provide (see the exposition of the general idea of the Tabernacle in § 3, and now in full detail by M‘Neile as cited, § 5 above). Nor must it be forgotten, that in reproducing in portable form, as they unquestionably do, the several parts and appointments of the Temple of Solomon, including even its brazen altar, the author or authors of the Tabernacle believed, in all good faith, that they were reproducing the essential features of the Mosaic sanctuary, of which the Temple was supposed to be the replica and the legitimate successor.

A. R. S. KENNEDY.

TABERNACLES, FEAST OF

1. OT references.—In Ex 23:16, 34:22 it is called the Feast of Ingathering, and its date is placed at the end of the year.

In Dt 16:13–15 its name is given as the Feast of Tabernacles or Booths ( possibly referring to the use of booths in the vineyard during the vintage). It is to last 7 days, to be observed at the central sanctuary, and to be an occasion of rejoicing. In the ‘year of release,’ i.e. the sabbatical year, the Law is to be publicly read (Dt 31:10–13). The dedication of Solomon’s Temple took place at this feast; in the account given in 1 K 8:66 the seven-day rule of Deut. is represented as being observed; but the parallel narrative of 2 Ch 7:8–10 assumes that the rule of Lev. was followed.

In Lv 23:34ff. and Nu 29:12–39 we find elaborate ordinances. The feast is to begin on 15th Tishri (October), and to last 8 days, the first and the last being days of holy convocation. The people are to live in booths improvised for the occasion. A very large number of offerings is ordained; on each of the first 7 days 2 rams and 14 Iambs, and a goat as a sin-offering; and successively on these days a diminishing number of bullocks: 13 on the 1st day, 12 on the 2nd, and so on till the 7th, when 7 were to be offered. On the 8th day the special offerings were 1 bullock, 1 ram, 7 lambs, and a goat as a sin-offering.

We hear in Ezr 3:4 of the observance of this feast, but are not told the method. The celebration in Neh 8:16 followed the regulations of Lev., but we are expressly informed that such had not been the case since Joshua’s days. Still, the feast was kept in some way, for Jeroboam instituted its equivalent for the Northern Kingdom in the 8th month (1 K 12:32, 33).

2. Character of the feast.—It was the Jewish harvest-home, when all the year’s produce of corn, wine, and oil had been gathered in; though no special offering of the earth’s fruits was made, as was done at the Feasts of Unleavened Bread and Pentecost. (The reason was perhaps a desire to avoid the unseemly scenes of the Canaanite vintage-festival, by omitting such a significant point of resemblance; cf. Jg 9:27.) It was also regarded as commemorating the Israelites’ wanderings in the wilderness. It was an occasion for great joy and the giving of presents; It was perhaps the most popular of the national festivals, and consequently the most generally attended. Thus Zec 14:16 names as the future sign of Judah’s triumph the fact that all the world shall come up yearly to Jerusalem to keep this festival.

3. Later customs.—In later times novel customs were attached to the observance. Such were the daily procession round the altar, with its sevenfold repetition on the 7th day; the singing of special Psalms; the procession on each of the first 7 days to Siloam to fetch water, which was mixed with wine in a golden pitcher, and poured at the foot of the altar while trumpets were blown (cf. Jn 7:37); and the illumination of the women’s court in the Temple by the lighting of the 4 golden candelabra (cf. Jn 8:12). The 8th day, though appearing originally as a supplementary addition to the feast, came to be regarded as an integral part of it, and is so treated in 2 Mac 10:6, as also by Josephus.

A. W. F. BLUNT.

TABITHA.—See DORCAS.

TABLE.—See HOUSE, § 8; MEALS, §§ 3, 4. For ‘Table of Shewbread’ see SHEWBREAD, TABERNACLE, § 6 (a), TEMPLE, §§ 5, 9, 12.

TABLE, TABLET.—1. Writing tablet is indicated by the Heb. lūach, which is also applied to wooden boards or planks (Ex 27:8, 38:7 in the altar of the Tabernacle, Ezk 27:5 in a ship, Ca 8:9 in a door) and to metal plates (in the bases of the lavers in Solomon’s Temple. 1 K 7:36). It is, however, most frequently applied to tables of stone on which the Decalogue was engraven (Ex 24:12, 31:18 etc.). It is used of a tablet on which a prophecy may be written (Is 30:8, Hab 2:2) , and in Pr 3:3, 7:3 and Jer 17:1 figuratively of the ‘tables of the heart.’ In all these passages, when used of stone, both AV and RV translate ‘table’ except in Is 30:8 where RV has ‘tablet.’ lūach generally appears in LXX and NT as plax (2 Co 3:3, He 9:4). The ‘writing table’ (RV ‘tablet’) of Lk 1:63 was probably of wax.

2. A female ornament is indicated by Heb. kūmāz, AV ‘tablets,’ RV ‘armlets,’ RVm ‘necklaces,’ Ex 35:22, Nu 31:50—probably a pendant worn on the neck.

The word ‘tablets’ is also the tr. of bottē hannephesh in AV Is 3:20 (RV ‘perfume boxes,’ lit. ‘houses of the soul’). It is doubtful if nephesh actually means ‘odour,’ but from meaning ‘breath’ it may have come to mean scent or smell. On the other hand, the idea of life may suggest that some life-giving elixir, scent, or ointment was contained in the vessels; but the meaning is doubtful.

The ‘tablet’ (gillāyōn) inscribed with a stylus to Maher-shalal-hash-baz, Is 8:1 (‘AV’ roll’), signifies a polished surface. The word occurs again in Is 3:23 where it probably refers to ‘tablets of polished metal’ used as mirrors (AV ‘glasses’).

W. F. BOYD.

TABOR.—1. A town in the tribe of Zebulun, given to Levites descended from Merari (1 Ch

6:77). Its site is unknown. Perhaps it is to be identified with Chislothtabor in the same tribe (Jos 19:12). 2. A place near Ophrah (Jg 8:18). 3. The Oak (AV ‘plain’) of Tabor was on the road from Ramah S. to Gibeah (1 S 10:3). 4. See next article.

H. L. WILLETT.

TABOR (MOUNT).—A mountain in the N.E. corner of the plain of Esdraelon, some 7 miles E. of Nazareth. Though only 1843 feet high, Tabor is, from its isolation and remarkable rounded shape, a most prominent object from great distances around; hence, though so very different in size from the great mountain mass of Hermon, it was yet associated with it (Ps 89:12). It was a king among the mountains (Jer 46:18). It is known to the Arabs as Jebel et-Tūr, lit. ‘the mountain of the mount,’ the same name as is applied to the Mount of Olives. From the summit of Tabor a magnificent outlook is obtained, especially to the W., over the great plain of Esdraelon to the mountains of Samaria and Carmel. It was on the borders of Zebulun and

Issachar (Jos 19:12, 22); It was certainly an early sanctuary, i and probably the reference in Dt

33:18 , 19 is to this mountain. Here the forces under Deborah and Barak rallied to fight Sisera (Jg 4:6, 12). Whether the reference in Jg 8:18 is to this mountain is doubtful. In later history Tabor appears chiefly as a fortress. In the 3rd cent. B.C., Antiochus the Great captured the city

Atabyrium which was upon Tabor, and afterwards fortified it. Between B.C. 105 and 78 the place was again in Jewish hands, but in B.C. 53 Gabinius here defeated Alexander, son of Aristobulus II., who was in revolt. A hundred and ten years later Josephus fortified the hill against Vespasian, but after the Jewish soldiers had been defeated by the general Placidus, the place surrendered. During the Crusades it was for long in the hands of the Christians, but fell to the Muslems after the battle of Hattin, and was fortified in 1212 by the successor of Saladin—a step which led to the inglorious and ineffectual 5th Crusade.

The tradition that Tabor was the scene of the Transfiguration goes back to the 3rd cent., but has little evidence in its favour. Although not directly recorded, the condition of the hill before and after would lead one to suppose that it was an inhabited site at the time of Christ, while the requirements of the Biblical narrative (Mk 8:27, 9:2–10, Lk 9:28–36) suggest a site near Cæsarea Philippi, such, for example, as an isolated spur of Hermon.

Mount Tabor to-day is one of the best-wooded spots in W. Palestine, groves of oaks and terebinths not only covering the hillsides, but extending also over a considerable area of hill and valley to the N.; game abounds in the coverts. The Franciscans and the Greek Church have each erected a monastery-hospice on the summit, and extensive excavations have been made, particularly by members of the former order. The foundations of a great wall of circumvallation—probably that of Josephus (BJ IV. i. 8)—have been followed, many ancient tombs have been cleared, and the remains of several churches of the 4th and of the 12th centuries have been unearthed.

E. W. G. MASTERMAN.

TABRET (see art. TABER) is AV tr. of tōph in Gn 31:27, 1 S 10:5, 18:6, Is 5:12, 24:8, 30:32,

Jer 31:4, Ezk 28:13. The same Heb. word is tr. ‘timbrel’ in Ex 15:20, Jg 11:34, 2 S 6:5, 1 Ch

13:8 , Job 21:12, Ps 81:2, 149:3, 150:4. It might have been well to drop both ‘timbrel’ and ‘tabret,’ neither of which conveys any clear sense to a modern ear, and adopt some such rendering as ‘tambourine’ or ‘hand-drum’. The AV rendering of Job 17:6 ‘aforetime I was as a tabret,’ has arisen from a confusion of tōpheth ‘spitting’ with tōph ‘tambourine.’ The words mean ‘I am become one to be spit on in the face’ (RV ‘an open abhorring’).

TABRIMMON.—The father of Benhadad (1 K 15:18).

TACHES.—An old word of French origin used by AV to render the Heb. qĕrāsīm, which occurs only in P’s description of the Tabernacle (Ex 26:6, 11, 33, 35:11 etc.). The Gr. rendering denotes the rings set in eyelets at the edge of a sail for the ropes to pass through. The Heb. word evidently signifies some form of hook or clasp (so RV) like the Roman fibula.

TACKLING in Is 33:23 means simply a ship’s ropes; in Ac 27:19 it is used more generally of the whole gearing (RVm ‘furniture’).

TADMOR (Palmyra).—In 2 Ch 8:4 we read that Solomon built ‘Tadmor in the [Syrian] desert.’ It has long been recognized that Tadmor is here a mistake for ‘Tamar in the [Judæan] desert’ of the corresponding passage in 1 Kings (9:18). The Chronicler, or one of his predecessors, no doubt thought it necessary to emend in this fashion a name that was scarcely known to him. (That it is really the city of Tadmor so famous in after times that is meant, is confirmed by the equally unhistorical details given in 2 Ch 8:3, 4 regarding the Syrian cities of Hamath and Zobah.) Hence arose the necessity for the Jewish schools to change the Tamar of 1

K 9:18 in turn into Tadmor [ the Qerē in that passage], so as to agree with the text of the

Chronicler. The LXX translator of 1 K 9:13 appears to have already had this correction before him. Nevertheless it is quite certain that Tamar is the original reading. But the correction supplies a very important evidence that at the time when Chronicles was composed (c. B.C. 200) , Tadmor was already a place of note, around the founding of which a fabulous splendour had gathered, so that it appeared fitting to attribute it to Solomon. This fiction maintained itself, and received further embellishments. The pre-Islamic poet Nābigha (v. 22 ff., ed. Ahlwardt, c. A.D.

600) relates that, by Divine command, the demons built Solomon’s Tadmor by forced labour. This piece of information he may have picked up locally; what he had in view would he, of course, the remains, which must have been still very majestic, of the city whose climax of splendour was reached in the 2nd and 3rd cent. A.D.

Tadmor, of whose origin and earlier history we know nothing, lay upon a great natural road through the desert, not far from the Euphrates, and not very far from Damascus. It was thus between Syria, Babylonia, and Mesopotamia proper. Since water, although not in great abundance, was also found on the spot, Tadmor supplied a peaceable and intelligent population with all the conditions necessary for a metropolis of the caravan trade. Such we find in the case of Palmyra, whose identity with Tadmor was all along maintained, and has recently been assured by numerous inscriptions. The first really historical mention of the place (B.C. 37 or 36) tells how the wealth of this centre of trade incited M. Antony to a pillaging campaign (Appian, Bell. Civ. v. 9).

The endings of the two names Tadmor and Palmyra are the same, but not the first syllable. It is not clear why the Westerns made such an alteration in the form. The name Palmyra can hardly have anything to do with palms. It would, indeed, be something very remarkable if in this Eastern district the Lat. palma was used at so early a date in the formation of names. The Oriental form Tadmor is to be kept quite apart from tāmār, ‘palm.’ Finally, it is unlikely that the palm was ever extensively cultivated on the spot.

Neither in the OT nor in the NT is there any other mention of Tadmor (Palmyra), and Josephus names it only when he reproduces the above passage of Chronicles (Ant. VIII. vi. 1). The place exercised, indeed, no considerable influence on the history either of ancient Israel or of early Christianity. There is therefore no occasion to go further into the history, once so glorious and finally so tragic, of the great city, or to deal with the fortunes of the later somewhat inconsiderable place, which now, in spite of its imposing ruins, is desolate in the extreme, but which still bears the ancient name Tadmor (Tedmur, Tudmur).

TH. NÖLDEKE.

TAHAN.—An Ephraimite clan (Nu 26:35 (39), 1 Ch 7:25); gentilic name Tahanites in Nu 26:35 (39).

TAHASH.—A son of Nahor (Gn 22:24).

TAHATH.—1. A Kohathite Levite (1 Ch 6:24). 2. 3. Two (unless the name has been accidentally repeated) Ephraimite families (1 Ch 7:20). 4. An unidentified ‘station’ of the Israelites (Nu 33:26f.).

TAHCHEMONITE (AV Tachmonite).—See HACHMONT.

TAHPANHES (Jer 2:16, 43:7ff., 44:1, 46:14, Ezk 30:18 (Tehaphnehes) , in Jth 1:9 AV Taphnes).—An Egyptian city, the same as the Greek Daphnæ, now Tett Defne. The Egyptian name is unknown. It lay on the Pelusiac branch of the Nile, which is now silted up, and the whole region converted into a waste. Petrie’s excavations showed that Daphnæ was founded by Psammetichus I. on the 26th Dyn. (B.C. 664–610). According to Herodotus, it was the frontier fortress of Egypt on the Asiatic side, and was garrisoned by Greeks. In its ruins was found an abundance of Greek pottery, iron armour, and arrowheads of bronze and iron, while numerous small weights bore testimony to the trade that passed through it. The garrison was kept up by the Persians in the 5th cent., and the town existed to a much later period. After the murder of Gedaliah (B.C. 586) , Johanan took the remnant of the Jews from Jerusalem, including Jeremiah, to Tahpanhes.

F. LL. GRIFFITH.

TAHPENES (1 K 11:19).—The name of Pharaoh’s wife, whose sister was given to Hadad the Edomite. It has the appearance of an Egyptian name, but has not yet been explained. The name of her son Genubath is not Egyptian. The Pharaoh should be of the weak 21st Dynasty. F. LL. GRIFFITH.

TAHREA.—A grandson of Mephibosheth (1 Ch 9:41); in 8:35 (prob. by a copyist’s error) Tarea.

TAHTIM HODSHI, THE LAND OF.—A place east of Jordan, which Joab and his officers visited when making the census for David (2 S 24:6). It is mentioned between Gilead and Danjaan. The MT, however, is certainly corrupt. In all probability we should read ha-HittimKādēshāh = ‘to the land of the Hittites, towards Kadesh [sc. Kadesh on the Orontes] .’

TALE.—‘Tale’ in AV generally means ‘number or sum,’ as Ex 5:18 ‘Yet shall ye deliver the tale of bricks.’ And the verb ‘to tell’ sometimes means ‘to number,’ as Gn 15:5 ‘Tell the stars, if thou be able to number them,’ where the same Heb. verb is translated ‘tell’ and ‘number.’

TALEBEARING.—See SLANDER.

TALENT.—See MONEY, WEIGHTS AND MEASURES.

TALITHA CUMI.—The command addressed by our Lord to the daughter of Jairus (Mk 5:41) , and interpreted by the Evangelist, ‘Maiden, I say unto thee, arise.’ The relating of the actual (Aramaic) words used by Jesus is characteristic of St. Mark’s graphic narrative; cf. 7:11, 34 , 14:36, 15:34.

TALMAI.—1. A clan resident in Hebron at the time of the Hebrew conquest and driven thence by Caleb (Nu 13:22, Jos 15:14, Jg 1:10). 2. Son of Ammihur (or Ammihud), king of Geshur, and a contemporary of David, to whom he gave his daughter Maacah in marriage (2 S 3:3 , 13:37, 1 Ch 3:2).

TALMON.—The name of a family of Temple gate-keepers (1 Ch 9:17, Ezr 2:42, Neh 7:45, 11:19, 12:25); called in 1 Es 5:28 Tolman. See, also, TELEM.

TALMUD ( ‘learning’ )

1. Origin and character.—The Jews have always drawn a distinction between the ‘Oral

Law,’ which was handed down for centuries by word of mouth, and the ‘Written Law,’ i.e. the

Pentateuch or Five Books of Moses. Both, according to Rabbinical teaching, trace their origin to

Moses himself. It has been a fundamental principle of all times that by the side of the ‘Written

Law,’ regarded as a summary of the principles and general laws of the Hebrew people, there was this ‘Oral Law’ to complete and explain the ‘Written Law.’ It was an article of faith that in the Pentateuch there was no precept and no regulation, ceremonial, doctrinal, or legal, of which God had not given to Moses all explanations necessary for their application, together with the order to transmit them by word of mouth. The classical passage on this subject runs: ‘Moses received the (oral) law from Sinai, and delivered it to Joshua, and Joshua to the elders, and the elders to the prophets, and the prophets to the men of the Great Synagogue’ (Pirqe Aboth, l. 1). This has long been known to be nothing more than a myth; the ‘Oral Law,’ although it no doubt contains elements which are of great antiquity—e.g. details of folklore—really dates from the time that the ‘Written Law’ was read and expounded in the synagogues. Thus we are told that Ezra introduced the custom of having the Torah (‘Law’) read in the synagogues at the morning service on Mondays and Thursdays (i.e. the days corresponding to these); for on these days the country people flocked to the towns from the neighbouring districts, as they were the market days. The people had thus an opportunity, which would otherwise have been lacking to them, of hearing the Law read and explained. These explanations of the Law, together with the results of the discussions of them on the part of the sōpherīm ( ‘scribes’), formed the actual ‘Oral Law.’ The first explanatory term applied by the Jews to the ‘Oral Law’ was midrash ( ‘investigation’), and the Bible itself witnesses to the way in which such investigations were made and expounded to the people: ‘Also Jeshua and Bani … and the Levites, caused the people to understand the law; and the people stood in their place. And they read in the book, in the law of God, with an interpretation; and they gave the sense, so that they understood the reading’ (Neh 8:7, 8). But it is clear that the ‘investigations’ must have led to different explanations; so that in order to fix authoritatively what in later days were considered the correct explanations, and thus to ensure continuity of teaching, it became necessary to reduce these to writing; there arose thus (soon after the time of Shammai and Hillel) the ‘Former Mishna’ (Mishna Rishonah), Mishna meaning ‘Second’ Law. This earliest Mishna, which, it is probable, owed its origin to pupils of Shammai and Hillel, was therefore compiled for the purpose of affording teachers both a norm for their decisions and a kind of book of reference for the explanation of difficult passages. But the immense amount of floating material could not be incorporated into one work, and when great teachers arose they sometimes found it necessary to compile their own Mishna; they excluded much which the official Mishna contained, and added other matter which they considered important. This was done by Rabbi Aqiba, Rabbi Meir, and others. But it was not long before the confusion created by this state of affairs again necessitated some authoritative, officially recognized action. It was then that Jehudah ha-Nasi undertook his great redaction of the Mishna, which has survived substantially to the present day. Jehudah ha-Nasi was born about A.D. 135 and died about A.D. 220 ; he was the first of Hillel’s successors to whose name was added the title ha-Nasi ( ‘the Prince’); this is the way in which he is usually referred to in Rabbinical writings; he is also spoken of as ‘Rabbi,’ i.e. master par excellence, and occasionally as ha-Qadosh, ‘the Holy,’ on account of his singularly pure and moral life. Owing to his authority and dignity, the Mishna of Jehudah ha-Nasi soon superseded all other collections, and became the only one used in the schools; the object that Jehudah had had in view, that, namely, of restoring uniform teaching, was thus achieved. The Mishna as we now have it is not, however, quite as it was when it left Jehudah’s hands; it has undergone modifications of various kinds: additions, emendations, and the like having been made even in Jehudah’s life-time, with his acquiescence, by some of his pupils. The language of the Mishna approximates to that of some of the latest books of the OT, and is known by the name of ‘Neo-Hebraic’; this was the language spoken in Palestine during

the second century A.D.; It has a considerable intermixture of foreign elements, especially Greek words Hebraized.

The Mishna is divided into six Sedarim (Aram. for ‘Orders’), and each Seder contains a number of treatises; each treatise is divided into chapters, and these again into paragraphs. The names of the six ‘Orders,’ which to some extent indicate their contents, are: Zera‘im ( ‘Seeds’), containing eleven treatises; Mo‘ed (‘Festival’), containing twelve treatises; Nashim (‘Women’), containing seven treatises; Nezikin ( ‘Injuries’), containing ten treatises [this ‘Order’ is called also Yeshu’oth (‘Deeds of help’)]; Qodashim ( ‘Holy things’), containing eleven treatises; and Tohāroth ( ‘Purifications’), containing twelve treatises.

Now the Mishna forms the basis of the Talmud; for just as the Mishna is a compilation of expositions, comments, etc., of the Written Law, and embodies in itself the Oral Law, so the Talmud is an expansion, by means of comment and explanation, of the Mishna; as the Mishna contains the Pentateuch, with all the additional explanatory matter, so the Talmud contains the Mishna with a great deal more additional matter. ‘The Talmud is practically a mere amplification of the Mishna by manifold comments and additions; so that even those portions of the Mishna which have no Talmud are regarded as component parts of it.… The history of the origin of the Talmud is the same as that of the Mishna—a tradition, transmitted orally for centuries, was finally cast into definite literary form, although from the moment in which the Talmud became the chief subject of study in the academies it had a double existence (see below), and was accordingly, in its final stage, redacted in two different forms’ (Bacher in JE xii. 3b) . Before coming to speak of the actual Talmud itself, it may be well to explain some terms without an understanding of which our whole subject would be very inadequately understood:—

Halakhah.—Under this term the entire legal body of Jewish oral tradition is included; it comes from a verb meaning ‘to go,’ and expresses the way ‘of going’ or ‘acting,’ i.e. custom, usage, which ultimately issues in law. Originally it was used in the plural form Halakhoth, which had reference to the multifarious civil and ritual laws, customs, decrees etc., as handed down by tradition, which were not, however, of Scriptural authority. It was these Halakboth which were codified by Jehudah ha-Nasi, and to which the term Mishna became applied. Sometimes the word Halakhah is used for ‘tradition,’ which is binding, in contradistinction to Dīn, ‘argument’ ( lit. ‘judgment’), which is not necessarily binding.

Haggadah (from the root meaning ‘to narrate’).—This includes the whole of the non-legal matter of Rabbinical literature, such as homilies, stories about Biblical saints and heroes; besides this it touches upon such subjects as astronomy, astrology, medicine, magic, philosophy, and all that would come under the term ‘folklore.’ This word, too, was originally used in the plural Haggadoth. Haggadah is also used in a special sense of the ritual for Passover Eve.

Gemara.—This is an Aramaic word from the root meaning ‘to learn,’ and has the signification of ‘that which has been learned,’ i.e. learning that has been handed down by tradition (Bacher in JE, art. ‘Talmud’); it has also the meaning ‘completion’; in this sense it came to be used as a synonym of Talmud.

Baraitha.—This is an apocryphal Halakhah. When Jehudah ha-Nasi compiled his Mishna, there was a great deal of the Oral Tradition which he excluded from it (see above); other teachers, however, the most important of whom was Rabbi Chijja, gathered these excluded portions into a special collection; these Halakhoth, which are known as Baraithoth, were incorporated into the Talmud; the discussions on them in the Talmud occupy many folios.

Tannaim (‘Teachers’).—This was the technical name applied to the teachers of the Mishna; after the close of the Mishna period those who explained it were no more called ‘Teachers,’ but only ‘Commentators’ (Amoraïm); the dicta of the Tannaim could not be questioned excepting by a Tannaite, but an exception was made in the case of Jehudah ha-Nasi, who was permitted to question the truth of Tannaite pronouncements.

There are two Talmuds, the ‘Jerusalem’ or ‘Talmud of Palestine’ and the ‘Babylonian,’ known respectively by their abbreviated forms ‘Yerushalmi’ and ‘Babli.’ The material which went to make up the Yerushalmi had been preparing in the academies, the centres of Jewish learning, of Palestine, chief among which was Tiberias; it was from here that Rabbi Jochanan issued the Yerushalmi, in its earliest form, during the middle of the 3rd cent. A.D. The first editor, or at all events the first compiler, of the Babli was Rabbi Ashi (d. A.D. 430) , who presided over the academy of Sura. Both these Talmuds were constantly being added to, and the Yerushalmi was not finally closed until the end of the 4th cent., the Babli not until the beginning of the 6th. The characteristics which differentiated the academies of Palestine from those of Babylonia have left their marks upon the two Talmuds: in Palestine the tendency was to preserve and stereotype tradition, without permitting it to develop itself along natural channels; the result was that the Yerushalmi became choked with traditionalism, circumscribed in its horizon, and in consequence was regarded with less veneration than the Babli, and has always occupied a position of subordinate importance in comparison with this latter. In the Babylonian academies, on the other band, there was a wider outlook, a freer mental atmosphere, and, while tradition was venerated, it was not permitted to impede development in all directions; the Babli therefore absorbed the thought and learning of all Israel’s teachers, and is richer in material, and of more importance generally, than the Yerushalmi. In order to give some idea of what the Talmud is, and of the enormous masses of material gathered together there, the following example may be cited, abbreviated from Bacher (op. cit. xii. 5). It will be remembered that the Talmud is a commentary on the Mishna. In the beginning of the latter occurs this paragraph: ‘During what time in the evening is the reading of the Shema‘ begun? From the time when the priests go in to eat their leaven (Lv 22:7) until the end of the first watch of the night, such being the words of R. Eliezer. The sages, however, say until midnight, though R. Gamaliel says until the coming of the dawn.’ This is the text upon which the Yerushalmi then comments in three sections; the first section contains the following: a citation from a bariatha with two sayings from R. Jose to elucidate it; remarks on the position of one who is in doubt whether he has read the Shema‘; another passage from a baraitha, designating the appearance of the stars as an indication of the time in question; further explanations and passages on the appearance of the stars as bearing on the ritual; other Rabbinical sayings; a baraitha on the division between day and night, and other passages bearing on the same subject; discussion of other baraithas, and further quotations from important Rabbis; a sentence of Tannaitic origin in no way related to the preceding matters, namely, ‘One who prays standing must bold his feet straight,’ and the controversy on this subject between Rabbis Levi and Simon, the one adding, ‘like the angels,’ the other, ‘like the priests’; comments on these two comparisons; further discussion concerning the beginning of the day; Haggadic statements concerning the dawn; a conversation between two Rabbis; cosmological comments; dimensions of the firmament, and more Haggadic comments in abundance; a discussion on the nightwatches; Haggadic material concerning David and his harp. Then comes the second section, namely, a Rabbinical quotation; a baraitha on the reading of the Shema‘ in the synagogue; other Rabbinical and Haggadic matter; further Haggadic sayings; lastly, section 3 gives R. Gamaliel’s view compared with that of another Rabbi, together with a question which remains unanswered.

This is, of course, the merest skeleton of an example of the mass of commentary which is devoted to the Mishna, section by section. Although the Haggadic element plays a much less Important rôle than the Halakhic, still the former is well represented, and is often employed for purposes of edification and rebuke, as well as for instruction. The following outline of a Haggadic passage from the Yerushalmi will serve as an example; It is intended as a rebuke to ‘Scandal-mongers,’ and a text (Dt 1:12) is taken as a starting-point, namely, ‘How can I myself alone bear your cumbrance and your burden and your strife?’ It then continues: ‘How did our forefathers worry Moses with their cumbrances? In that they were constantly slandering him, and imputing evil intentions to him in everything that he did. If he happened to come out of his house rather earlier than usual, it was said: “Why has he gone out so early to-day? There has no doubt been some quarrelling at home!” If, on the other hand, he went out a little later than usual, it was said: “What has been occupying him so long indoors? Assuredly he has been concocting plans to oppress the people yet morel” ’ (Bernfeld, Der Talmud, p. 46). Or, to give one other example: in pointing out the evils which come from a father’s favouring one son above the others, it is said: ‘This should not be done, for because of the coat of many colours which the patriarch Jacob gave his favourite son Joseph (Gn 37:1ff.), all Israel went down into Egypt’ (ib. p. 47).

Haggadoth flourish, as regards quality, more in the Yerushalmi than in the Babli; for in the Babylonian schools intellectual acumen reigned supreme: there was but little room for the play of the emotions or for the development of poetical imagination: these were rather the property of Palestinian soil. Therefore, although the Haggadic element is, so far as quantity is concerned, much fuller in the Babli than in the Yerushalmi, it is, generally speaking, of a far less attractive character in the former than in the latter. ‘The fact that the Haggadah is much more prominent in Babli, of which it forms, according to Weiss, more than one-third, while it constitutes only onesixth of Yerushalmi, was due, in a sense, to the course of the development of Hebrew literature. No independent mass of Haggadoth developed in Babylon, as was the case in Palestine; and the Haggadic writings were accordingly collected in the Talmud’ (JE xii. 12). But the Haggadah, whether in the Yerushalmi or in the Babli, occupies in reality a subordinate place, for in its origin, as we have seen, the Talmud was a commentary on the Mishna, which was a collection of

Halakhoth; and although the Haggadic portions are of much greater human interest, it is the Halakhic portions that form the bulk of the Talmud, and that constitute its importance as the fountain-head of Jewish belief and theology.

2. Authority of the Talmud.—Inasmuch as the Oral Law, which with its comments and explanations is what constitutes the Talmud, is regarded as of equal authority with the Written Law, it will be clear that the Talmud is regarded, at all events by orthodox Jews, as the highest and final authority on all matters of faith. It is true that in the Talmud itself the letter of Scripture is always clearly differentiated from the rest; but, in the first place, the comments and explanations declare what Scripture means, and without this official explanation the Scriptural passage would lose much of its practical value for the Jew; and, in the second place, it is firmly believed that the oral laws preserved in the Talmud were delivered to Moses on Mount Sinai. It is therefore no exaggeration to say that the Talmud is of equal authority with Scripture. The eighth principle of the Jewish creed runs: ‘I firmly believe that the Law which we possess now is the same which has been given to Moses on Mount Sinai.’ In commenting on this in what may not unjustly be described as the official handbook for the orthodox Jewish Religion, the writer says: ‘Many explanations and details of the laws were supplemented by oral teaching; they were handed down by word of mouth from generation to generation, and only after the destruction of the second temple were they committed to writing. The latter are, nevertheless, called Oral Law, as distinguished from the Torah or Written Law, which from the first was committed to writing. Those oral laws which were revealed to Moses on Mount Sinai are called “Laws given to Moses on Mount Sinai” ’ (M. Friedländer, The Jewish Religion [ revised and enlarged ed., 1900], p. 136) . It is clear from this that the Written Law of the Bible, and the Oral Law as contained in the

Talmud, are of equal authority. The Talmud is again referred to as ‘the final authority in

Judaism’ by the writer of a later exposition of the Jewish faith (M. Joseph, Judaism as Creed and Life, 1903, p. vii.). One other authoritative teacher may be quoted: ‘As a document of religion the Talmud acquired that authority which was due to it as the written embodiment of the ancient tradition, and it fulfilled the task which the men of the Great Assembly set for the representatives of the tradition when they said, “Make a hedge for the Torah” (Aboth, i. 2). Those who professed Judaism felt no doubt that the Talmud was equal to the Bible as a source of instruction and decision in problems of religion, and every effort to set forth religious teachings and duties was based on it.’ And speaking of the present day, the same writer says: ‘For the majority of Jews it is still the supreme authority in religion’ (Bacher in JE xii. 26).

3. The Talmud and Christianity.—Much that is written in the Talmud was originally spoken by men who were contemporaries of Christ; men who must have seen and heard Him. It is, moreover, well known what a conflict was waged in the infant Church regarding that question of the admittance of Gentiles, the result of which was an irreconcilable breach between Jew and Gentile, and an ever-increasing antagonism between Judaism and Christianity. These facts lead to the supposition that references to Christ and Christianity should be found in the Talmud. The question as to whether such references are to be found or not is one which cannot yet be said to have been decided one way or the other. The frequent mention of the Minim is held by many to refer to Christians; others maintain that by these are meant philosophizing Jews, who were regarded as heretics. This is not the place to discuss the question; we can only refer to two works, which approach it from different points of view, and which deal very adequately with it:

Christianity in Talmud and Midrash, by R. T. Herford (London, 1903), and Die religiösen

Bewegungen innerhalb des Judenthums im Zeitatter Jesu, by M. Friedländer (Berlin, 1905).

W. O. E. OESTERLEY.

TAMAR.—1. A Canaanite woman, married to Er and then to his brother Onan (see

MARRIAGE, 4). Tamar became by her father-in-law himself the mother of twin sons, Perez and Zerah (Gn 38, Ru 4:12, 1 Ch 2:4, Mt 1:3). 2. The beautiful sister of Absalom, who was violated and brutally insulted by her half-brother, Amnon (2 S 13:1ff.). 3. A daughter of Absalom (2 S 14:27). 4. See next article.

TAMAR.—In Ezk 47:19, 48:28 the S.E. boundary-mark of the restored kingdom of Israel. No proposed identification has been successful, since no place of this name has been found in the region required, that is, near the S. end of the Dead Sea. It is possibly the same place that is mentioned in 1 K 9:18 as one of the S. fortresses built up by Solomon. Here a variant Heb.

reading has Tadmor (wh. see)—a manifest error, which is perhaps borrowed from the parallel passage 2 Ch 8:4.

J. F. MCCURDY.

TAMARISK (’ēshel).—This name occurs in RV (only) three times; Gn 21:33 AV ‘grove,’ mg. ‘tree’; 1 S 22:6 AV ‘tree,’ mg. ‘grove’; 1 S 31:13 AV ‘tree.’ The RV rendering is based upon an identification of the Heb. ’ēshel with the Arab. ’āthl. RVm gives ‘tamarisk’ for heath of EV in Jer 17:6 (cf. 48:6), but probably a species of juniper is intended here. There are some eight species of tamarisks in Palestine; they are most common in the Maritime Plain and the Jordan Valley. Though mostly but shrubs, some species attain to the size of large trees. They are characterized by their brittle feathery branches and minute scale-like leaves.

E. W. G. MASTERMAN.

TAMMUZ ( Ezk 8:14) was a Babylonian god whose worship spread into Phœnicia. The name appears to be Sumerian, Dumuzi, Tamuzu, and may mean ‘son of life.’ He was a form of the Sun-god and bridegroom of Ishtar. He was celebrated as a shepherd, cut off in early life or slain by the boar (winter). Ishtar descended to Hades to bring him back to life. He was mourned on the second of the month Tammuz (June). His Canaanite name Adonai gave rise to the Greek Adonis, and he was later identified with the Egyptian Osiris. In Am 8:10 and Zec 12:10 the mourning for ‘the only son’ may be a reference to this annual mourning, and the words of the refrain, ‘Ah me, ah me l’ (Jer 22:18) may be recalled.

C. H. W. JOHNS.

TANHUMETH.—The father (?) of Seraiah, one of the Heb. captains who joined Gedaliah at Mizpah (2 K 25:23, Jer 40:8).

TANIS (Jth 1:10).—See ZOAN.

TANNER.—See ARTS AND CRAFTS, 5.

TAPHATH.—Daughter of Solomon and wife of Ben-abinadab (1 K 4:11).

TAPPUAH.—1. A ‘son’ of Hebron (1 Ch 2:43). Probably the name is that of a town in the Shephēlah (Jos 15:34. It was probably to the N. of Wādy es-Sunt, but the site has not been recovered. 2. See EN-TAPPUAH. 3. One of the towns W. of Jordan whose kings Joshua smote (Jos 12:17). It was perhaps the same place as No. 2 above; but this is by no means certain. See also TIPHSAH and TEPHON.

TARALAH.—An unknown town of Benjamin (Jos 18:27).

TAREA.—See TAHREA.

TARES (Gr. zizania, Arab. zuwān) are certain kinds of darnel growing plentifully in cornfields. The bearded darnel (Lolium temulentum) most resembles wheat. The seeds, though often poisonous to human beings on account of parasitic growths in them, are sold as chicken’s food. When harvest approaches and the tares can be distinguished, they are carefully weeded out by hand by women and children (cf. Mt 13:24–30).

E. W. G. MASTERMAN.

TARGET.—See ARMOUR ARMS, 2.

TARGUMS.—Originally the word targum meant ‘translation’ in reference to any language; but it acquired a restricted meaning, and came to be used only of translation from Hebrew into Aramaic. As early as the time of Ezra we find the verb used in reference to a document written in Aramaic (Ezr 4:7), though in this passage the addition ‘in Aramaic’ is made, showing that the restricted meaning had not yet come into vogue. As early as the time of the Second Temple the language of the Holy Scriptures, Hebrew, was not understood by the bulk of the Jewish people, for it had been supplanted by Aramaic. When, therefore, the Scriptures were read in synagogues, it became necessary to translate them, in order that they might be understood by the congregation. The official translator who performed this duty was called the methurgeman or targeman, which is equivalent to the modern dragoman ( ‘interpreter’). The way in which it was done was as follows:—In the case of the Pentateuch (the ‘Law’) a verse was read in Hebrew, and then translated into Aramaic, and so on to the end of the appointed portion; but in the case of the prophetical writings three verses were read and then translated. Whether this system was the custom originally may be doubted; it was probably done in a less formal way at first. By degrees the translation became stereotyped, and was ultimately reduced to writing; and thus the Targums, the Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Bible, came into existence. The various Targums which are still extant will be enumerated below. As literary products they are of late date, but they occupy a highly important place in post-Biblical Jewish religious literature, because they embody the traditional exegesis of the Scriptures. They have for many centuries ceased to be used in the synagogue; from the 9th cent. onwards their use has been discontinued. It is, however, interesting to note an exception in the case of Southern Arabia, where the custom still survives; and in Bokhara the Persian Jews read the Targum, with the Persian paraphrase of it, to the lesson from the Prophets for the last day of the Passover Feast, namely, Is 10:32–12 . There are Targums to all the books of the Bible, with the exception of Daniel, Ezra, and Nehemiah; as these are to a large extent written in Aramaic, one can understand why Targums to these books should be wanting. Most of the Targums are mainly paraphrases; the only one which is in the form of a translation in the modern sense of the word is the Targum of Onkelos to the,

Pentateuch; this is, on the whole, a fairly literal translation. Isolated passages in the Bible which are written in Aramaic, as in Genesis and Jeremiah, are also called Targums. The following is a list of the Targums which are in existence:

1. Targum of Onkelos to the Pentateuch, called also Targum Babli, i.e. the Babylonian Targum.

2. The Palestinian Targum to the Pentateuch, called also Targum Jerushalmi, i.e. the Jerusalem Targum.

3. The ‘Fragment Targum’ to the Pentateuch.

4. The Targum of Jonathan to the prophetical books (these include what we call the historical books ).

5. The Targum Jerushalmi to the prophetical books.

6. The Targum to the Psalms.

7. The Targum to Job.

8. The Targum to Proverbs.

9–13. The Targums to the Five Megilloth ( ‘Rolls’), namely: Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, Esther; the Book of Esther has three Targums to it.

14 . The Targum to Chronicles.

For printed editions of these, reference may be made to the bibliographies given in Schürer, HJP I. i.

pp. 160–163, and in the JE xii. 63.

To come now to a brief description of these Targums:

The Targum of Onkelos is the oldest of all the Targums that have come down to us; it is for the most part a literal translation of the Pentateuch, only here and there assuming the form of a paraphrase. The name of this Targum owes its origin to a passage in the Babylonian Talmud (Megillah, 3a), in which it is said: ‘The Targum to the Pentateuch was composed by the proselyte Onkelos at the dictation of Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Joshua’; and in the Jerusalem Talmud (Megillah, 71c) it is said: ‘Aquila the proselyte translated the Pentateuch in the presence of Rabbi Eliezer and Rabbi Joshua. That Aquila is the same as Onkelos can scarcely admit of doubt. In the tractate Abodah zara, 11a, we are told that this Onkelos was the pupil of Rabbi Gamaliel the Elder, who lived in the second half of the 1st cent. A.D. Seeing that this Targum rests on tradition, it will be clear that we have in it an ancient witness to Jewish exegesis; indeed, it is the earliest example of Midrashic tradition that we possess; and not only so, but as this Targum is mainly a translation, it is a most important authority for the pre-Massoretic text of the Pentateuch. This shows of what high value the Targum of Onkelos is, and that it is not without reason that it has always been regarded with great veneration. It is characteristic of the Targum of Onkelos that, unlike the other Targums, the Midrashic element is greatly subordinated to simple translation; when it does appear it is mainly in poetic passages, though not exclusively (cf. Gn 49, Nu 24, Dt 32, 33, which are prophetic in character. The idea apparently was that greater licence was permitted in dealing with passages of this kind than with those in which the legal element predominated. As with the Targums generally, so with that of Onkelos, there is a marked tendency to avoid anthropomorphisms and expressions which might appear derogatory to the dignity of God; this may be seen, for example, in Gn 11:4, where the words ‘The Lord came down,’ which seemed anthropomorphic, are rendered in this Targum, ‘the Lord revealed Himself.’ Then again, the transcendent character of the Almighty is emphasized by substituting for the Divine Person intermediate agencies like the Memra, or ‘Word’ of God, the Shekinah, or ‘Glory’ of God, to which a more or less distinct personality is imputed; in this way it was sought to avoid ascribing to God Himself actions or words which were deemed unfitting to the inexpressible majesty and transcendence of the Almighty. A good example of this, and one which will also illustrate the general character of this Targum, is the following; it is the rendering of Gn 3:8ff. ‘And they heard the voice of the Word (Memra) of the Lord God walking in the garden in the evening of the day; and Adam and his wife hid themselves from before the Lord God among the trees of the garden. And the Lord God called to Adam and said: “Where art thou?” And he said: “The voice of Thy Word (Memra) I heard in the garden, and I was afraid, because I was naked, and I would hide.” ’

The other Targum to the Pentateuch, the Targum Jerushalmi, has come down to us in two forms: one in a complete form, the other only in fragments, hence the name of the latter which is generally used, the ‘Fragment Targum.’ The fragments have been gathered from a variety of sources, from manuscripts and from quotations found in the writings of ancient authors. But owing to its fragmentary character this Targum is of much less value than the ‘Targum

Jerushalmi.’ This latter is sometimes erroneously called the ‘Targum of Jonathan ben Uzziel on the Pentateuch’; but though this Jonathan was believed to be the author of the Targum to the Prophets which bears his name (see below), there was not the slightest ground for ascribing to him the authorship of the Targum to the Pentateuch (‘Targum Jerushalmi’). The mistake arose in an interesting way. In its abbreviated form this Targum was referred to as ‘Targum J’; this ‘J,’ which of course stood for ‘Jerushalmi,’ was taken to refer to ‘Jonathan,’ the generally

acknowledged author of the Targum to the Prophets; thus it came about that this Targum to the Pentateuch, as well as the Targum to the Prophets, was called the Targum of Jonathan. So tenaciously has the wrong name clung to this Targum, that a kind of compromise is made as to its title, and it is now usually known as the ‘Targum of pseudo-Jonatban.’ In one important respect this Targum is quite similar to that of Onkelos, namely, in its avoidance of anthropomorphisms, and in its desire not to bring God into too close contact with man; for example, in Ex 34:6 we have these words: ‘And the Lord descended in a cloud, and stood with him there, and proclaimed the name of the Lord.’ But this Targum paraphrases the verse in a roundabout way, and says that ‘Jehovah revealed Himself in the clouds of the glory of His Shekinah,’ thus avoiding what in the original text appeared to detract from the dignity of the Almighty. This kind of thing occurs with great frequency, and it is both interesting and important, as showing the evolution of the idea of God among the Jews (see Oesterley and Box, The Religion and Worship of the Synagogue, ch. viii. [1907]). But in other respects the ‘Targum Jerushalmi’ (or ‘Targum of pseudo-Jonathan’) differs from that of Onkelos, especially in its being far less a translation than a free paraphrase. The following extract will give a good idea of the character of this Targum; It is the paraphrase of Gn 18:1ff. ‘And the glory of the Lord was revealed to him in the valley of Mamre; and he, being ill from the pain of circumcision, sat at the door of the tabernacle in the beat of the day. And he lifted up his eyes and looked, and behold, three angels in the resemblance of men were standing before him; angels who had been sent from the necessity of three things—because it is not possible for a ministering angel to be sent for more than one purpose at a time—one, then, had come to make known to him that Sarah should bear a man-child; one had come to deliver Lot; and one to overthrow Sodom and Gomorrah. And when he saw them, he ran to meet them from the door of the tent, and bowed himself to the earth.’