JABESH.—Father of Shallum, who usurped the kingdom of Israel by the assassination of king Zechariah (2 K 15:10, 13, 14).

JABESH, JABESH-GILEAD.—A city which first appears in the story of the restoration of the Benjamites (Jg 21). Probably it bad not fully recovered from this blow when it was almost forced to submit to the disgraceful terms of Nahash the Ammonite (1 S 11). In gratitude for Saul’s relief of the city, the Inhabitants rescued his body from maltreatment by the Philistines (1 S 31:11–13)—an act which earned them the commendation of David (2 S 2:4).

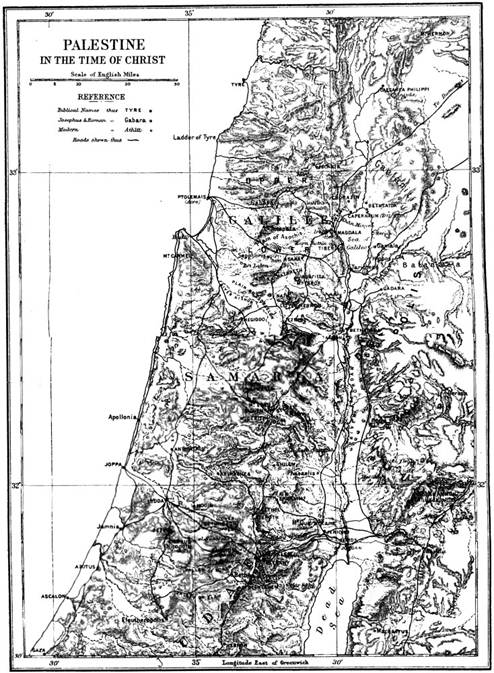

According to the Onomasticon, the site is 6 Roman miles from Pella. The name seems to be preserved in Yabis, a wady tributary to the Jordan, which runs down at the south part of transJordanic Manasseh. The site itself, however, is not yet identified with certainty.

R. A. S. MACALISTER.

JABEZ.—1. A city in Judah occupied by scribes, the descendants of Caleb (1 Ch 2:55). 2. A man of the family of Judah, noted for his ‘honourable’ character (1 Ch 4:9ff.); called Ya’bēts, which is rendered as if it stood for Ya’tsēb, ‘he causes pain.’ In his vow (v. 10) there is again a play upon his name.

W. EWING.

JABIN (‘[God] perceives’).—A Canaanite king who reigned in Hazor, a place near the Waters of Merom, not far from Kedesh. In the account, in Jg 4, of the defeat of Jabin’s host under Sisera, the former takes up quite a subordinate position. In another account (Jos 11:1–9) of this episode the victory of the two tribes of Zebulun and Naphtali is represented as a conquest of the whole of northern Canaan by Joshua. Both accounts (Jos 11:1–9, Jg 4) are fragments taken from an earlier, and more elaborate, source; the Jabin in each passage is therefore one and the same person.

W. O. E. OESTERLEY.

JABNEEL.—1. A town on the N. border of Judah, near Mt. Baalah, and close to the sea ( Jos 15:11). In 2 Ch 26:6 it is mentioned under the name Jabneh, along with Gath and Ashdod, as one of the cities captured from the Philistines by Uzziah. Although these are the only OT references, it is frequently mentioned (under the name Jamnia) in the Books of Maccabees (1 Mac 4:15, 5:58, 10:69, 15:40, 2 Mac 12:8, 9, 40) and in Josephus. Judas is said to have burned its harbour; it was captured by Simon from the Syrians. In Jth 2:28 it is called Jemnaan. After various vicissitudes it was captured in the war of the Jews by Vespasian. After the destruction of Jerusalem, Jabneel, now called Jamnia, became the home of the Sanhedrin. At the time of the Crusades the castle Ibelin stood on the site. To-day the village of Yebna stands on the ruined remains of these ancient occupations. It stands 170 feet above the sea on a prominent hill S. of the Wady Rubin. The ancient Majumas or harbour of Jamnia lies to the West. ‘The port would seem to be naturally better than any along the coast of Palestine S. of Cæsarea’ ( Warren ).

2. An unknown site on the N. boundary of Naphtali not far from the Jordan (Jos 19:33).

E. W. G. MASTERMAN.

JABNEH.—See JABNEEL.

JACAN.—A Gadite chief (1 Ch 5:13).

JACHIN.—1. Fourth son of Simeon (Gn 46:10, Ex 6:15) called in 1 Ch 4:24 Jarib; in Nu

26:12 the patronymic Jachinites occurs. 2. Eponym of a priestly family (1 Ch 9:10, Neh 11:10).

JACHIN AND BOAZ.—These are the names borne by two brazen, or more probably

bronze, pillars belonging to Solomon’s Temple. They evidently represented the highest artistic achievement of their author, Hiram of Tyre,’ the half-Tyrian copper-worker, whom Solomon fetched from Tyre to do foundry work for him,’ whose name, however, was more probably Huram-abi (2 Ch 2:12, Heb. text). The description of them now found in 1 K 7:15–22 is exceedingly confused and corrupt, but with the help of the better preserved Gr. text, and of other OT. references (viz. 7:41, 42, 2 Ch 3:15–17, 4:12, 13 and Jer 52:21–23 = 2 K 25:17), recent scholars have restored the text of the primary passage somewhat as follows:—

And he cast the two pillars of bronze for the porch of the temple; 18 cubits was the height of the one pillar, and a line of 12 cubits could compass it about, and its thickness was 4 finger bread the (for it was) hollow [with this cf. Jer 52:21]. And the second pillar was similar. And he made two chapiters [i.e. capitals] of cast bronze for the tops of the pillars, etc. [as in RV]. And he made two sets of network to cover the chapiters which were upon the tops of the pillars, a network for the one chapiter and a network for the second chapiter. And he made the pomegranates; and two rows of pomegranates in bronze were upon the one network, and the pomegranates were 200, round about upon the one chapiter, and so he did for the second chapiter. And be set up the pillars at the porch of the temple,’ etc. [as in v. 21 RV].

The original description, thus freed from later glosses such as the difficult ‘lily work’ of v. 19, consists of three parts; the pillars, their capitals, and the ornamentation of the latter. The pillars themselves were hollow, with a thickness of metal equal to three inches of our measure; their height, on the basis of the larger cubit of 201/2 inches (see Hastings’ DB iv. 907a), was about 31 feet, while their diameter works out at about 61/2 feet. The capitals appear from 1 K 7:41 to have been globular or spheroidal in form, each about 81/2 feet in height, giving a total height for the complete pillars of roughly 40 feet. The ornamentation of the capitals was twofold: first they were covered with a specially cast network of bronze. Over this were hung festoon-wise two wreaths of bronze pomegranates, each row containing 100 pomegranates, of which it is probable that four were fixed to the network, while the remaining 96 hung free (see Jer 52:23).

As regards their position relative to the Temple, it may be regarded as certain that they were structurally independent of the Temple porch, and stood free in front of it—probably on plinths or bases—Jachin on the south and Boaz on the north (1 K 7:21), one on either side of the steps leading up to the entrance to the porch (cf. Ezk 40:49). Such free-standing pillars were a feature of Phœnician and other temples of Western Asia, the statements of Greek writers on this point being confirmed by representations on contemporary coins. A glass dish, discovered in Rome in 1882, even shows a representation of Solomon’s Temple with the twin pillars flanking the porch, as above described (reproduced in Benzinger’s Heb. Arch. [1907], 218).

The names ‘Jachin’ and ‘Boaz’ present an enigma which still awaits solution. The meanings suggested in the margins of EV—Jachin, ‘he shall establish,’ Boaz, ‘in it is strength’—give no help, and are besides very problematical. The various forms of the names presented by the Greek texts—for which see EBi ii. 2304 f. and esp. Barnes in JThSt v. [1904], 447–551–point to a possible original nomenclature as Baal and Jachun—the latter a Phœnician verbal form of the same signification (‘he will be’) as the Heb. Jahweh.

The original significance and purpose of the pillars, finally, are almost as obscure as their names. The fact that they were the work of a Phœnician artist, however, makes it probable that their presence is to be explained on the analogy of the similar pillars of Phœnician temples. These, though viewed in more primitive times as the abode of the Deity (see PILLAR), had, as civilization and religion advanced, come to be regarded as mere symbols of His presence. To a Phœnician temple-builder, Jachin and Boaz would appear as the natural adjuncts of such a building, and are therefore, perhaps, best explained as conventional symbols of the God for whose worship the Temple of Solomon was designed.

For another, and entirely improbable, view of their original purpose, namely, that they were huge candelabra or cressets in which ‘the suet of the sacrifices, was burned, see W. R. Smith’s RS 2, 488; and for the latest attempts to explain the pillars in terms of the Babylonian ‘astral mythology,’ see A. Jeremias, Das alte Test. im Lichte d. alt. Orients 2 [1906], 494, etc.; Benzinger, op. cit., 2nd ed. [1907] , 323, 331.

A. R. S. KENNEDY.

JACINTH.—See JEWELS AND PRECIOUS STONES, p. 467a.

JACKAL.—Although the word ‘jackal’ does not occur in the AV, there is no doubt that this animal is several times mentioned in OT: it occurs several times in RV where AV has ‘fox.’ (1) shū’āl is used in Heb. for both animals, but most of the references are most suitably tr. ‘jackal.’

The only OT passage in which the fox is probably intended is Neh 4:3. (2) tannīm (pl.), AV

‘dragons,’ is in RV usually tr. ‘jackals.’ See Is 34:13, Jer 9:11, 10:22 etc. Post considers

‘wolves’ would be better. (3) ’iyyīm, tr. AV ‘wild beasts of the island’ (Is 13:22, 34:14, Jer 50:39), is in RV tr. ‘wolves,’ but Post thinks these ‘howling creatures’ (as word implies) were more probably jackals. (4) ’ōhīm, ‘doleful creatures’ (Is 13:21), may also have been jackals. The jackal (Canis aureus) is exceedingly common in Palestine; its mournful cries are heard every night. During the day jackals hide in deserted ruins, etc. (Is 13:22, 34:13, 35:7), but as soon as the sun sets they issue forth. They may at such times be frequently seen gliding backwards and forwards across the roads seeking for morsels of food. Their staple food is carrion of all sorts (Ps 63:10). At the present day the Bedouin threaten an enemy with death by saying they will ‘throw his body to the jackals.’ Though harmless to grown men when solitary, a whole pack may be dangerous. The writer knows of a case where a European was pursued for miles over the Philistine plain by a pack of jackals. It is because they go in packs that we take the shu’ālim of Jg 15:4 to be jackals rather than foxes. Both animals have a weakness for grapes ( Ca 2:15). Cf. art. Fox.

E. W. G. MASTERMAN.

JACOB.—1. Son of Isaac and Rebekah. His name is probably an elliptical form of an original Jakob’el, ‘God follows’ (i.e. ‘rewards’), which has been found both on Babylonian tablets and on the pylons of the temple of Karnak. By the time of Jacob this earlier history of the word was overlooked or forgotten, and the name was understood as meaning ‘one who takes by the heel, and thus tries to trip up or supplant’ (Gn 25:26, 27:36, Hos 12:3). His history is recounted in Gn 25:21–50:13, the materials being unequally contributed from three sources. For the details of analysis see Dillmann, Com., and Driver, LOT3, p. 16. P supplies but a brief outline; J and E are closely interwoven, though a degree of original independence is shown by an occasional divergence in tradition, which adds to the credibility of the joint narrative.

Jacob was born in answer to prayer (25:21), near Beersheba; and the later rivalry between

Israel and Edom was thought of as prefigured in the strife of the twins in the womb (25:22f., 2 Es 3:16, 6:8–10, Ro 9:11–13). The differences between the two brothers, each contrasting with the other in character and habit, were marked from the beginning. Jacob grew up a ‘quiet man’ ( Gn 25:27 RVm), a shepherd and herdsman. Whilst still at home, he succeeded in overreaching Esau in two ways. He took advantage of Esau’s hunger and heedlessness to secure the birthright, which gave him precedence even during the father’s lifetime (43:33), and afterwards a double portion of the patrimony (Dt 21:17), with probably the domestic priesthood. At a later time, after careful consideration (Gn 27:11ff.), he adopted the device suggested by his mother, and, allaying with ingenious falsehoods (27:20) his father’s suspicion, intercepted also his blessing. Isaac was dismayed, but instead of revoking the blessing confirmed it (27:33–37), and was not able to remove Esau’s bitterness. In both blessings later political and geographical conditions are reflected. To Jacob is promised Canaan, a well-watered land of fields and vineyards (Dt 11:14 , 33:28), with sovereignty over its peoples, even those who were ‘brethren’ or descended from the same ancestry as Israel (Gn 19:37f., 2 S 8:12, 14). Esau is consigned to the dry and rocky districts of Idumæa, with a life of war and plunder; but his subjection to Jacob is limited in duration (2 K 8:22), if not also in completeness (Gn 27:40f., which points to the restlessness of Edom).

Of this successful craft on Jacob’s part the natural result on Esau’s was hatred and resentment, to avoid which Jacob left his home to spend a few days (27:44) with his uncle in Haran. Two different motives are assigned. JE represents Rebekah as pleading with her son his danger from Esau; but P represents her as suggesting to Isaac the danger that Jacob might marry a Hittite wife (27:46). The traditions appear on literary grounds to have come from different sources; but there is no real difficulty in the narrative as it stands. Not only are man’s motives often complex; but a woman would be likely to use different pleas to a husband and to a son, and if a mother can counsel her son to yield to his fear, a father would be more alive to the possibility of an outbreak of folly. On his way to Haran, Jacob passed a night at Bethel (cf. 13:3f.), and his sleep was, not unnaturally, disturbed by dreams; the cromlechs and stone terraces of the district seemed to arrange themselves into a ladder reaching from earth to heaven, with angels ascending and descending, whilst Jehovah Himself bent over him (28:13 RVm) with loving assurances. Reminded thus of the watchful providence of God, Jacob’s alarms were transmuted into religions awe. He marked the sanctity of the spot by setting up as a sacred pillar the boulder on which his head had rested, and undertook to dedicate a tithe of all his gains. Thence forward Bethel became a famous sanctuary, and Jacob himself visited it again (35:1; cf. Hos 12:4).

Arrived at Haran, Jacob met in his uncle his superior for a time in the art of overreaching. By a ruse Laban secured fourteen years’ service (29:27, Hos 12:12, Jth 8:26), to which six years more were added, under an ingenious arrangement in which the exacting uncle was at last outwitted (30:31ff.). At the end of the term Jacob was the head of a household conspicuous even in those days for its magnitude and prosperity. Quarrels with Laban and his sons ensued, but God is represented as intervening to turn their arbitrary actions (31:7ff.) to Jacob’s advantage. At length he took flight whilst Laban was engaged in sheep-shearing, and, re-crossing the Euphrates on his way home, reached Gilead. There he was overtaken by Laban, whose exasperation was increased by the fact that his teraphim, or household gods, had been taken away by the fugitives, Rachel’s hope in stealing them being to appropriate the good fortune of her fathers. The dispute that followed was closed by an alliance of friendship, the double covenant being sealed by setting up in commemoration a cairn with a solitary boulder by its side (31:45f., 52), and by sharing a sacrificial meal. Jacob promised to treat Laban’s daughters with special kindness, and both Jacob and Laban undertook to respect the boundary they had agreed upon between the territories of Israel and of the Syrians. Thereupon Laban returned home; and Jacob continued his journey to Canaan, and was met by the angels of God (32:1), as if to congratulate and welcome him as he approached the Land of Promise.

Jacobs next problem was to conciliate his brother, who was reported to be advancing against him with a large body of men (32:6). Three measures were adopted. When a submissive message elicited no response, Jacob in dismay turned to God, though without any expression of regret for the deceit by which he had wronged his brother, and proceeded to divide his party into two companies, in the hope that one at least would escape, and to try to appease Esau with a great gift. The next night came the turning-point in Jacob’s life. Hitherto he had been ambitious, steady of purpose, subject to genuine religious feeling, but given up almost wholly to the use of crooked methods. Now the higher elements in his nature gain the ascendency; and henceforth, though he is no less resourceful and politic, his fear of God ceases to be spoilt by intervening passions or a competing self-confidence. Alone on the banks of the Jabbok (Wady Zerka), full of doubt as to the fate that would overtake him, he recognizes at last that his real antagonist is not Esau but God. All his fraud and deceit had been pre-eminently sin against God; and what he needed supremely was not reconciliation with his brother, but the blessing of God. So vivid was the impression, that the entire night seemed to be spent in actual wrestling with a living man. His thigh was sprained in the contest; but since his will was so fixed that he simply would not be refused, the blessing came with the daybreak (32:28). His name was changed to Israel, which means etymologically ‘God perseveres,’ but was applied to Jacob in the sense of ‘Perseverer with God’ (Hos 12:3f.). And as a name was to a Hebrew a symbol of nature (Is 1:26, 61:3), its change was a symbol of a changed character; and the supplanter became the one who persevered in putting forth his strength in communion with God, and therefore prevailed. His brother received him cordially (33:4), and offered to escort him during the rest of the journey. The offer was courteously declined, ostensibly because of the difference of pace between the two companies, but probably also with a view to incur no obligation and to risk no rupture. Esau returned to Seir; and Jacob moved on to a suitable site for an encampment, which received the name of Succoth, from the booths that were erected on it (33:17). It was east of the Jordan, and probably not far from the junction with the Jabbok. The valley was suitable for the recuperation of the flocks and herds after so long a journey; and it is probable, from the character of the buildings erected, as well as from the fact that opportunity must be given for Dinah, one of the youngest of the children (30:21), to reach a marriageable age (34:2ff.), that Jacob stayed there for several years.

After a residence of uncertain length at Succoth, Jacob crossed the Jordan and advanced to Shechem, where he purchased a plot of ground which became afterwards of special interest. Joshua seems to have regarded it as the limit of his expedition, and there the Law was promulgated and Joseph’s hones were buried (Jos 24:25, 32; cf. Ac 7:16); and for a time it was the centre of the confederation of the northern tribes (1 K 12:1, 2 Ch 10:1). Again Jacob’s stay must not be measured by days; for he erected an altar (33:20) and dug a well (Jn 4:6, 12), and was detained by domestic troubles, if not of his own original intention. The troubles began with the seduction or outrage of Dinah; but the narrative that follows is evidently compacted of two traditions. According to the one, the transaction was personal, and involved a fulfilment by Shechem of a certain unspecified condition; according to the other, the entire clan was involved on either side, and the story is that of the danger of the absorption of Israel by the local Canaanites and its avoidance through the interposition of Simeon and Levi. But most of the difficulties disappear on the assumption that Shechem’s marriage was, as was natural, expedited, a delight to himself and generally approved amongst his kindred (34:19). That pressing matter being settled, the question of an alliance between the two cians, with the sinister motives that prevailed on either side, would be gradually, perhaps slowly, brought to an issue. There would be time to persuade the Shechemites to consent to be circumcised, and to arrange for the treacherous reprisai. Jacob’s part in the proceedings was confined chiefly to a timid reproach of his sons for entangling his household in peril, to which they replied with the plea that the honour of the family was the first consideration.

The state of feeling aroused by the vengeance executed on Shechem made it desirable for Jacob to continue his journey. He was directed by God to proceed some twenty miles southwards to Bethel. Before starting, due preparations were made for a visit to so sacred a spot. The amulets and images of foreign gods in the possession of his retainers were collected and huried under a terebinth (35:4; cf. Jos 24:26, Jg 9:6). The people through whom he passed were smitten with such a panic by the news of what had happened at Shechem as not to interfere with him. Arrived at Bethel, he added an altar (35:7) to the monolith he had erected on his previous visit, and received in a theophany, for which in mood he was well prepared, a renewal of the promise of regal prosperity. The additional pillar he set up (35:14) was probably a sepulchral stele to the memory of Deborah (cf. 35:20), dedicated with appropriate religious services; unless the verse is out of place in the narrative, and is really J’s version of what E relates in 28:18. From Bethel Jacob led his caravan to Ephrath, a few miles from which place Rachel died in childbirth. This

Ephrath was evidently not far from Bethel, and well to the north of Jerusalem (1 S 10:2f., Jer

31:15); and therefore the gloss ‘the same is Bethlehem’ must be due to a confusion with the other Ephrath (Ru 4:11, Mic 5:2), which was south of Jerusalem. The next stopping-place was the tower of Eder (35:21) or ‘the flock’—a generic name for the watch-towers erected to aid in the protection of the flocks from robbers and wild beasts. Mic 4:8 applies a similar term to the fortified southern spur of Zion. But it cannot he proved that the two allusions coalesce; and actually nothing is known of the site of Jacob’s encampment, except that it was between Ephrath and Hebron. His journey was ended when he reached the last-named place (35:27), the home of his fathers, where he met Esau again, and apparently for the last time, at the funeral of Isaac.

From the time of his return to Hebron, Jacob ceases to be the central figure of the Biblical narrative, which thenceforward revolves round Joseph. Among the leading incidents are Joseph’s mission to inquire after his brethren’s welfare, the inconsolable sorrow of the old man on the receipt of what seemed conclusive evidence of Joseph’s death, the despatch of his surviving sons except Benjamin to buy corn in Egypt (cf. Ac 7:12ff.), the bitterness of the reproach with which he greeted them on their return, and his belated and despairing consent to another expedition as the only alternative to death from famine. The story turns next to Jacob’s delight at the news that Joseph is alive, and to his own journey to Egypt through Beersheha, his early home, where he was encouraged by God in visions of the night (46:1–7). In Egypt he was met by Joseph, and, after an interview with the Pharaoh, settled in the pastoral district of Goshen (47:6), afterwards known as ‘the land of Rameses’ (from Rameses II. of the nineteenth dynasty), in the eastern part of the Delta (47:11). This migration of Jacob to Egypt was an event of the first magnitude in the history of Israel (Dt 26:5f., Ac 7:14f.), as a stage in the great providential preparation for Redemption. Jacob lived in Egypt seventeen years (47:28), at the close of which, feeling death to be nigh, he extracted a pledge from Joseph to bury him in Canaan, and adopted his two grandsons, placing the younger first in anticipation of the pre-eminence of the tribe that would descend from him (48:19, He 11:21). To Joseph himself was promised, as a token of special affection, the conquered districts of Shechem on the lower slopes of Gerizim (48:22, Jn 4:5). Finally, the old man gathered his sons about him, and pronounced upon each in turn a blessing, afterwards wrought up into the elaborate poetical form of 49:2–27. The tribes are reviewed in order, and the character of each is sketched in a description of that of its founder. The atmosphere of the poem in regard alike to geography and to history is that of the period of the judges and early kings, when, therefore, the genuine tradition must have taken the form in which it has been preserved. After blessing his sons, Jacob gave them together the directions concerning his funeral which he had given previously to Joseph, and died (49:33). His body was embalmed, convoyed to Canaan by a great procession according to the Egyptian custom, and buried in the cave of Machpeiah near Hebron (50:13).

Opinion is divided as to the degree to which Jacob has been idealized in the Biblical story. If it be remembered that the narrative is based upon popular oral tradition, and did not receive its present form until long after the time to which it relates, and that an interest in national origins is both natural and distinctly manifested in parts of Genesis, some idealization may readily he conceded. It may be sought in three directions—in the attempt to find explanations of existing institutions, in the anticipation of religious conceptions and sentiments that belonged to the narrator’s times, and in the investment of the reputed ancestor with the characteristics of the tribe descended from him. All the conditions are best met by the view that Jacob was a real person, and that the incidents recorded of him are substantially historical. His character, as depicted, is a mixture of evil and good; and his career shows how, by discipline and grace, the better elements came to prevail, and God was enabled to use a faulty man for a great purpose.

2. Father of Joseph, the husband of Mary (Mt 1:15f.).

R. W. MOSS.

JACOB’S WELL.—See SYCHAR.

JACUBUS (1 Es 9:48) = Neh 8:7 Akkub.

JADA.—A Jerahmeelite (1 Ch 2:28, 32).

JADDUA.—1. One of those who sealed the covenant (Neh 10:21). 2. A high priest ( Neh 12:11, 22). He is doubtless the Jaddua who is named by Josephus in connexion with Alexander the Great (Jos. Ant. XI. viii. 5, cf. vii. 2, viii. 7).

JADDUS (AV Addus).—A priest whose descendants were unable to trace their genealogy at the return under Zerub., and were removed from the priesthood (1 Es 5:38). He is there said to have married Augia, a daughter of Zorzelleus or Barzillai, and to have been called after his name. In Ezr 2:61 and Neh 7:63 he is called by his adopted name Barziliai.

JADON.—A Meronothite, who took part in rebuilding the wail of Jerusalem (Neh 3:7). The title ‘Meronothite’ occurs again 1 Ch 27:30, but a place Meronoth is nowhere named. According to Jos. (Ant. VIII. viii. 5, ix. 1), Jadon was the name of the man of God sent from Judah to Jeroboam (1 K 13).

JAEL.—The wife of Heber, the Kenite (Jg 4:11, 17). The Kenites were on friendly terms both with the Israelites (1:16) and with the Canaanites, to whom Jabin and his general, Sisera, belonged. On his defeat by the Israelites, Sisera fled to the tent of Jaei, a spot which was doubly secure to the fugitive, on account both of intertribal friendship and of the rules of Oriental hospitality. The act of treachery whereby Jael slew Sisera (Jg 4:21) was therefore of the basest kind, according to the morals of her own time, and also to modern ideas. The praise, therefore, accorded to Jael and her deed in the Song of Deborah (Jg 5:24–27) must be accounted for on the questionable moral principle that an evil deed, if productive of advantage, may be rejoiced over and commended by those who have not taken part in it. The writer of the Song of Deborah records an act which, though base, resulted in putting the seal to the Israelite victory, and thus contributed to the recovery of Israel from a ‘mighty oppression’ (Jg 4:3); in the exultation over this result the woman who helped to bring it about by her act is extolled. Though the writer of the Song would probably have scorned to commit such a deed himself, he sees no incongruity in praising it for its beneficent consequences. This is one degree worse than ‘doing evil that good may come,’ for the evil itself is extolled; whereas, in the other case, it is deplored, and unwillingly acquiesced in because it is ‘necessary.’ The spirit which praises such an act as Jael’s is, in some sense, akin to that of a Jewish custom (Corban) which grew up in later days, and which received the condemnation of Christ, Mk 7:11; in each case a contemptible act is condoned, and even extolled, because of the advantage (of one kind or another) which it brings.

In Jg 5:6 the words ‘in the days of Jael’ create a difficulty, which can be accounted for only by regarding them, with most scholars, as a gloss. See also BARAK, DEBORAH, SISERA.

W. O. E. OESTERLEY.

JAGUR.—A town in the extreme south of Judah (Jos 15:21). The site is unknown.

JAH.—See GOD, § 2 (g).

JAHATH.—1. A grandson of Judah (1 Ch 4:2). 2. A great-grandson of Levi (1 Ch 6:20, 43). 3. A son of Shimei (1 Ch 23:10). 4. One of the ‘sons’ of Shelomoth (1 Ch 24:22). 5. A Merarite Levite in the time of Josiah (2 Ch 34:12).

JAHAZ (in 1 Ch 6:78, Jer 48:21 Jahzah).—A town at which Sihon was defeated by Israel (Nu 21:23, Dt 2:32, Jg 11:20). After the crossing of the Arnon, messengers were sent to Sihon from the ‘wilderness of Kedemoth’ (Dt 2:26), and he ‘went out against Israel into the wilderness and came to Jahaz’ (Nu 21:23). Jahaz is mentioned in connexion with Kedemoth (Jos 13:18 , 21:36). These passages indicate a position for Jahaz in the S. E. portion of Sihon’s territory.

Jahaz was one of the Levite cities of Reuben belonging to the children of Merari (Jos 13:18 ,

21:36 (see note in RVm], 1 Ch 6:78). According to the Moabite Stone (11:18–20), the king of Israel dwelt at Jahaz while at war with king Mesha, but was driven out, and the town was taken and added to Moabite territory. Isaiah (15:4) and Jeremiah (48:21, 34) refer to it as in the possession of Moab. The site has not yet been identified.

JAHAZIEL.—1. A Benjamite who joined David at Ziklag (1 Ch 12:4). 2. One of the two priests who blew trumpets before the ark when it was brought by David to Jerusalem (1 Ch 16:6). 3. A Kohathite Levite (1 Ch 23:19, 24:23). 4. An Asaphite Levite who encouraged Jehoshaphat and his army against an invading host (2 Ch 20:14). 5. The ancestor of a family of exiles who returned (Ezr 8:5); called in 1 Es 8:32 Jezelus.

JAHDAI.—A Calebite (1 Ch 2:47).

JAHDIEL.—A Manassite chief (1 Ch 5:24).

JAHDO.—A Gadite (1 Ch 5:14).

JAHLEEL.—Third son of Zebulun (Gn 46:14, Nu 26:25); patron. Jahleelites (Nu 26:25).

JAHMAI.—A man of Issachar (1 Ch 7:2).

JAHWEH.—See GOD, § 2 (f).

JAHZAH.—The form of Jahaz (wh. see) in 1 Ch 6:78 and Jer 48:21.

JAHZEEL.—Naphtah’s firstborn (Gn 46:24, Nu 26:48); in 1 Ch 7:13 Jahziel; patron. Jahzeelites (Nu 26:48).

JAHZEIAH.—One of four men who are mentioned as opposing (so RV) Ezra in the matter of the foreign wives (Ezr 10:15). The AV regarded Jahzeiah and his companions as supporters of Ezra, rendering ‘were employed about this matter.’ This view is supported by LXX, 1 Es 9:14 RVm; but the Heb. phrase here found elsewhere (cf. 1 Ch 21:1, 2 Ch 20:23, Dn 11:14) expresses opposition.

JAHZERAH.—A priest (1 Ch 9:12); called in Neh 11:13 Ahzai.

JAHZIEL.—See JAHZEEL.

JAIR.—1. A clan of Jairites lived on the east of Jordan who were called after Jair. This Jair was of the children of Manasseh (Nu 32:41), and—if we may assume a traditional fusion—a ‘judge’ (Jg 10:3ff.). The settlement of this clan marks a subsequent conquest to that of the west of Jordan. The gentilic Jairite is used for Ira (2 S 20:26). 2. The father of Mordecai (Est 2:5), 3.

The father of Elhanan. See ELHANAN, JAARE-OREGIM).

W. F. COBB.

JAIRUS (= Jair).—This Greek form of the name is used in the Apocrypha (Ad. Est 11:2) for Mordecai’s father Jair (Est 2:5); and (1 Es 5:31) for the head of a family of Temple servants. In

NT it is the name of the ruler of the synagogue whose daughter Jesus raised from the dead ( Mk 5:22, Lk 8:41). In || Mt. (9:18) he is not named. The story of this raising comes from the ‘Petrine tradition.’

A. J. MACLEAN.

JAKEH.—Father of Agur, the author of the proverbs contained in Pr 30.

JAKIM.—1. A Benjamite (1 Ch 8:19). 2. A priest, head of the 12th course (1 Ch 24:12).

JALAM.—A ‘son’ of Esau (Gn 36:5, 14, 18, 1 Ch 1:35).

JALON.—A Calebite (1 Ch 4:17).

JAMBRES.—See JANNES AND JAMBRES.

JAMBRI.—A robber tribe which attacked and captured a convoy under the charge of John the Maccabee. The outrage was avenged by Jonathan and Simon, who waylaid and slaughtered a large party of the ‘sons of Jambri’ (1 Mac 9:35–42).

JAMES

1. James, the son of Zehedee, one of the Twelve, the elder brother of John. Their father was a Galilæan fisherman, evidently in a thriving way, since he employed ‘hired servants’ (Mk 1:20). Their mother was Salome, and, since she was apparently a sister of the Virgin Mary (cf. Mt

27:56 = Mk 15:40 with Jn 19:25), they were cousins of Jesus after the flesh. Like his brother, James worked with Zebedee in partnership with Simon and Andrew (Lk 5:10), and he was busy with boat and nets when Jesus called him to leave all and follow Him (Mt 4:21, 22 = Mk 1:19 , 20). His name is coupled with John’s in the lists of the Apostles (Mt 10:2 = Mk 3:17 = Lk 6:14) , which means that, when the Twelve were sent out two by two to preach the Kingdom of God (Mk 6:7), they wentin company. And they seem to have been men of like spirit. They got from Jesus the same appellation, ‘the Sons of Thunder’ (see BOANERGES), and they stood, with Simon Peter, on terms of special intimacy with Him. James attained less distinction than his brother, but the reason is not that he had less devotion or aptitude, but that his life came to an untimely end.

He was martyred by Herod Agrippa (Ac 12:2).

2. James, the son of Alphæus (probably identical with Clopas of Jn 19:25 RV), styled ‘the Little’ (not ‘the Less’), probably on account of the shortness of his stature, to distinguish him from the other Apostle James, the son of Zebedee. His mother was Mary, one of the devoted women who stood by the Cross and visited the Sepulchre. He had a brother Joses, who was apparently a believer. See Mk 15:40, Jn 19:25, Mk 16:1.

Tradition says that he had been a tax-gatherer, and it is very possible that his father Alphæus was the same person as Alphæus the father of Levi the tax-gatherer (Mk 2:14), afterwards Matthew the Apostle and Evangelist. If these identifications he admitted, that family was indeed highly favoured. It gave to the Kingdom of heaven a father, a mother, and three sons, of whom two were Apostles.

3. James, the Lord’s brother (see BRETHREN OF THE LORD). Like the rest of the Lord’s brethren, James did not believe in Him while He lived, but acknowledged His claims after the Resurrection. He was won to faith by a special manifestation of the risen Lord (1 Co 15:7). Thereafter he rose to high eminence. He was the head of the Church at Jerusalem, and figures in that capacity on three occasions. (1) Three years after his conversion Paul went up to Jerusalem to interview Peter, and, though he stayed for fifteen days with him, he saw no one else except James (Gal 1:18, 19.). So soon did James’s authority rival Peter’s. (2) After an interval of fourteen years Paul went up again to Jerusalem (Gal 2:1–10). This was the occasion of the historic conference regarding the terms on which the Gentiles should be admitted into the Christian Church; and James acted as president, his decision being unanimously accepted ( Ac 15:4–34). (3) James was the acknowledged head of the Church at Jerusalem, and when Paul returned from his third missionary journey he waited on him and made a report to him in presence of the elders (Ac 21:18, 19).

According to extra-canonical tradition, James was surnamed ‘the Just’; he was a Nazirite from his mother’s womb, abstaining from strong drink and animal food, and wearing linen; he was always kneeling in intercession for the people, so that his knees were callous like a camel’s; he was cruelly martyred by the Scribes and Pharisees: they cast him down from the pinnacle of the Temple (cf. Mt 4:5 , Lk 4:9), and as the fall did not kill him, they stoned him, and he was finally despatched with a fuller’s club.

This James was the author of the NT Epistle which bears his name; and it is an indication of his character that he styles himself there (1:1) not ‘the brother,’ but the ‘servant of the Lord Jesus Christ.’ See next article.

4. James, the father of the Apostle Judas (Lk 6:16 RV), otherwise unknown. The AV ‘Judas the brother of James’ is an impossible identification of the Apostle Judas with the author of the Epistle (Jude 1).

DAVID SMITH.

JAMES, EPISTLE OF

1. The author claims to be ‘James, a servant of God, and of the Lord Jesus Christ’ (1:1). He is usually identified with the Lord’s brother the ‘bishop’ of Jerusalem, not a member of the Twelve, but an apostle in the wider sense (see JAMES, 3). The name is common, and the writer adds no further note of identification. This fact makes for the authenticity of the address. If the Epistle had been pseudonymous, the writer would have defined the position of the James whose authority he wished to claim, and the same objection holds good against any theory of interpolation. Or again, if it had been written by a later James under his own name, he must have distinguished himself from his better known namesakes. The absence of description supports the common view of the authorship of the letter; it is a mark of modesty, the brother of the Lord not wishing to insist on his relationship after the flesh; it also points to a consciousness of authority; the writer expected to be listened to, and knew that his mere name was a sufficient description of himself. So Jude writes merely as ‘the brother of James.’ It has indeed been doubted whether a Jew of his position could have written such good Greek as we find in this Epistle, but we know really very little of the scope of Jewish education; there was every opportunity for intercourse with Greeks in Galilee, and a priori arguments of this nature can at most be only subsidiary. If indeed the late date, suggested by some, be adopted, the possibility of the brother of the Lord being the author is excluded, since he probably died in 62; otherwise there is nothing against the ordinary view. If that be rejected, the author is entirely unknown. More will be said in the rest of the article on the subject; but attention must be called to the remarkable coincidence in language between this Epistle and the speech of James in Ac 15.

2. Date.—The only indications of date are derived from indirect internal evidence, the interpretation of which depends on the view taken of the main problems raised by the Epistle. It is variously put, either as one of the earliest of NT writings (so Mayor and most English writers), or among the very latest (the general German opinion). The chief problem is the relationships to other writings of the NT. The Epistle has striking resemblances to several books of the NT, and these resemblances admit of very various explanations.

(a) Most important is its relation to St Paul. It has points of contact with Romans: 1:22, 4:11 and Ro 2:13 (hearers and doers of the law); 1:2–4 and Ro 5:3–5 (the gradual work of temptation or tribulation); 4:11 and Ro 2:1, 14:4 (the critic self-condemned); 1:21, 4:1 and Ro 7:23, 13:12 ; and the contrast between 2:21 and Ro 4:1 (the faith of Abraham). Putting the latter aside for the moment, it is hard to pronounce on the question of priority. Sanday-Headlam (Romans, p. lxxix.) see ‘no resemblance in style sufficient to prove literary connexion’; there are no parallels in order, and similarities of language can mostly be explained from OT and LXX. Mayor, on the other hand, supposes that St. Paul is working up hints received from James.

The main question turns upon the apparent opposition between James and Paul with regard to ‘faith and works.’ The chief passages are ch. 2, esp. vv. 17, 21ff., and Ro 3:28, 4, Gal 2:16. Both writers quote Gn 15:6, and deal with the case of Abraham as typical, but they draw from it apparently opposite conclusions—St. James that a man is justified, as Abraham was, by works and not by faith alone; St. Paul that justification is not by works but by faith. We may say at once with regard to the doctrinal question that it is generally recognized that there is here no real contradiction between the two. The writers mean different things by ‘faith.’ St. James means a certain belief, mainly intellectual, in the one God (2:19), the fundamental creed of the Jew, to which a belief in Christ has been added. To St. Paul ‘faith’ is essentially ‘faith in Christ’ ( Ro 3:22, 26 etc.). This faith has been in his own experience a tremendous overmastering force, bringing with it a convulsion of his whole nature; he has put on Christ, died with Him, and risen to a new life. Such an experience lies outside the experience of a St. James, a typically ‘good’ man, with a practical, matter of fact, and somewhat limited view of life. To him ‘conduct is three-fourths of life,’ and he claims rightly that men shall authenticate in practice their verbal professions. To a St. Paul, with an overwhelming experience working on a mystical temperament, such a demand is almost meaningless. To him faith is the new life in Christ, and of course it brings forth the fruits of the Spirit, if it exists at all; faith must always work by love (Gal 5:6). He indeed guards himself carefully against any idea that belief in the sense of verbal confession or intellectual assent is enough in itself (Ro 2:6–20), and defines ‘the works’ which he disparages as ‘works of the law’ (3:20, 28). Each writer, in fact, would agree with the doctrine of the other when he came to understand it, though St. James’s would appear to St. Paul as insufficient, and St. Paul’s to St. James as somewhat too profound and mystical (see SandayHeadlam, Romans, pp. 102 ff.).

It is unfortunately not so easy to explain the literary relation between the two. At first sight the points of contact are so striking that we are inclined to say that one must have seen the words of the other. Lightfoot, however, has shown (Galatians3, pp. 157 ff.) that the history of Abraham, and in particular Gn 15:6, figured frequently in Jewish theological discussions. The verse is quoted in 1 Mac 2:52, ten times by Philo, and in the Talmudic treatise Mechilta. But the antithesis between ‘faith and works’ seems to be essentially Christian; we cannot, therefore, on the ground of the Jewish use of Gn 15, deny any relationship between the writings of the two Apostles. This much, at least, seems clear; St. James was not writing with Romans before him, and with the deliberate intention of contradicting St. Paul. His arguments, so regarded, are obviously inadequate, and make no attempt, even superficially, to meet St. Paul’s real position. It is, however, quite possible that he may have written as he did to correct not St. Paul himself, but misunderstandings of his teaching, which no doubt easily arose (2 P 3:16). On the other hand, if with Mayor we adopt a very early date for the Epistle, St. Paul may equally well be combating exaggerations of his fellow-Apostle’s position, which indeed in itself must have appeared insufficient to him; we are reminded of the Judaizers ‘who came from James’ before the Council (Ac 15:24). St. Paul, according to this view, preserves all that is valuable in St. James by his insistence on life and conduct, while he supplements it with a profounder teaching, and guards against misinterpretations by a more careful definition of terms; e.g. in Gal 2:16 (cf. Ja 2:24) he defines ‘works’ as ‘works of the law,’ and ‘faith’ as ‘faith in Jesus Christ.’ We must also bear in mind the possibility that the resemblance in language on this and other subjects may have been due to personal intercourse between the two (Gal 1:19, Ac 15); in discussing these questions together they may well have come to use very similar terms and illustrations; and this possibility makes the question of priority in writing still more complicated. It is, then, very hard to pronounce with any certainty on the date of the Epistle from literary considerations. On the whole they make for an early date. Such a date is also suggested by the undeveloped theology (note the nontechnical and unusual word for ‘begat’ in 1:18) and the general circumstances of the Epistle (see below); and the absence of any reference to the Gentile controversy may indicate a date before the Council of Ac 15, i.e. before 52 A.D.

(b) Again, the points of contact with 1 Peter (1:10, 5:19; 1 P 1:24, 4:8) and Hebrews (2:25 ; He 11:31), though striking, are inconclusive as to date. It is difficult to acquiesce in the view that James is ‘secondary’ throughout, and makes a general use of the Epp. of NT.

(c) It will be convenient to treat here the relation to the Gospels and particularly to the Sermon on the Mount, though this is still less decisive as to date. The variations are too strong to allow us to suppose a direct use of the Gospels; the sayings of Christ were long quoted in varying forms, and in 5:12 St. James has a remarkable agreement with Justin (Ap, i. 16), as against Mt 5:37. The chief parallels are the condemnation of ‘hearers only’ (1:22, 25, Mt 7:25, Jn 13:17), of critics (4:11, Mt 7:1–5), of worldliness (1:10, 2:5, 6 etc., Mt 6:19, 24, Lk 6:24); the teaching about prayer (1:5 etc., Mt 7:7, Mk 11:23), poverty (2:5, Lk 6:20), humility (4:10, Mt 23:12), the tree and its fruits (3:11, Mt 7:16; see Salmon, Introd. to NT 9 p. 455). This familiarity with our Lord’s language agrees well with the hypothesis that the author was one who had been brought up in the same home, and had often listened to His teaching, though not originally a disciple; it can hardly, however, he said necessarily to imply such a close personal relationship.

3. The type of Christianity implied in the Epistle.—We are at once struck by the fact that the direct Christian references are very few. Christ is only twice mentioned by name (1:1, 2:21) ; not a word is said of His death or resurrection, His example of patience (5:10, 11; contrast 1 P 2:21), or of prayer (5:17; contrast He 5:7). Hence the suggestion has been made by Spitta that we have really a Jewish document which has been adapted by a Christian writer, as happened, e.g., with 2 Esdras and the Didache. The answer is obvious, that no editor would have been satisfied with so slight a revision. We find, indeed, on looking closer, that the Christian element is greater than appears at first, and also that it is of such a nature that it cannot be regarded as interpolated. The parallels with our Lord’s teaching already noticed, could not be explained as due to independent borrowing from earlier Jewish sources, even on the very doubtful assumption that any such existed containing the substance of His teaching. Again, we find Christ mentioned (probably) in connexion with the Parousia (5:7, 8) [5:6, 11 are probably not references to the crucifixion, and ‘the Lord’ is not original in 1:12]; ‘beloved brethren’ (1:16, 19, 2:5), the new birth (1:18), the Kingdom (2:5), the name which is blasphemed (2:7), and the royal law of liberty (1:25, 2:8) are all predominantly Christian ideas. It cannot, however, be denied that the general tone of the Epistle is Judaic. The type of organization implied is primitive, and is described mainly in Jewish phraseology: synagogue (2:2), elders of the Church (5:14), anointing with oil and the connexion of sin and sickness (ib.). Abraham is ‘our father’ (2:21), and God bears the OT title ‘Lord of Sabaoth’ (5:4) [only here in NT]. This tone, however, is in harmony with the traditional character of James (see JAMES, 3), and with the address ‘to the twelve tribes which are of the Dispersion’ (1:1), taken in its literal sense. St. James remained to the end of his life a strict Jew, noted for his devotion to the Law (Ac 15, 21:20), and in the Epistle the Law, though transformed, is to the writer almost a synonym for the Gospel. His argument as to the paramount importance of conduct is exactly suited to the atmosphere in which he lived, and of which he realized the dangers. The Rabbis could teach that ‘they cool the flames of Gehinnom for him who reads the Shema [Dt 6:4],’ and Justin (Dial. 141) bears witness to the claim of the Jews, ‘that if they are sinners and know God, the Lord will not impute to them sin.’ His protest is against a ceremonialism which neglects the weightier matters of the Law; cf. esp. 1:27, where ‘religion’ means religion on its outward side. His Epistle then is Judaic, because it shows us Christianity as it appeared to the ordinary Jewish Christian, to whom it was a something added to his old religion, not a revolutionary force altering its whole character, as it was to St. Paul. It seems to belong to the period described in the early chapters of the Acts, when the separation between Jews and Christians was not complete; we have already, on other grounds, seen that it seems to come before the Council. Salmon (Introd. to NT p. 456) points out that its attitude towards the rich agrees with what we know of Jewish society during this period, when the tyranny of the wealthy Sadducean party was at its height (cf. Jos. Ant. XX. viii. 8; ix. 2); there are still apparently local Jewish tribunals (2:6). The movement from city to city supposed in 4:13 may point to the frequent Jewish migrations for purposes of trade, and the authority which the writer exercises over the Diaspora may be paralleled by that which the Sanhedrin claimed outside Palestine. We may note that there are indications that the Epistle has in mind the needs and circumstances of special communities (2:1ff., 4:1, 5:13); it reads, too, not like a formal treatise, but as words of advice given in view of particular cases.

On the other hand, many Continental critics see in these conditions the description of a later age, when Christianity had had time to become formal and secularized, and moral degeneracy was covered by intellectual orthodoxy. The address is supposed to be a literary device, the Church being the true Israel of God, or to have in view scattered Essene conventicles. It is said that the absence of Christian doctrine shows that the Epistle was not written when it was in the process of formation, but at an altogether later period. This argument is not altogether easy to follow, and, as we have seen, the indications, though separately indecisive, yet all combine to point to an early date. Perhaps more may be said for the view that the Epistle incorporates Jewish fragments, e.g. in 3:1–18, 4:11–5:6; the apostrophe of the rich who are outside the brotherhood is rather startling. We may indeed believe that the Epistle has not yet yielded its full secret. It cannot be denied that it omits much that we should expect to find in a Christian document of however early a date, and that its close is very abrupt. Of the theories, however, which have so far been advanced, the view that it is a primitive Christian writing at least presents the fewest difficulties, though it still leaves much unexplained.

4. Early quotations and canonicity.—The Epistle presents points of contact with Clement of Rome, Hermas, and probably with Irenæns, but is first quoted as Scripture by Origen. Eusebius, though he quotes it himself without reserve, mentions the fact that few ‘old writers’ have done so (HE ii. 23), and classes it among the ‘disputed’ books of the Canon (iii. 25). It is not mentioned in the Muratorian Fragment, but is included in the Peshitta (the Syriac version), together with 1 Peter and 1 John of the Catholic Epistles. The evidence shows that it was acknowledged in the East earlier than in the West, possibly as being addressed to the Eastern ( ? ) Dispersion, though its apparent use by Clem. Rom. and Hermas suggests that it may have been written in Rome. The scarcity of quotations from it and its comparative neglect may be due to its Jewish and non-doctrinal tone, as well as to the facts that it did not claim to be Apostolic and seemed to contradict St. Paul. Others before Luther may well have found it ‘an epistle of straw.’

5. Style and teaching.—As has been said, the tone of the Epistle is largely Judaic. In addition to the Jewish features already pointed out, we may note its insistence on righteousness, and its praise of wisdom and poverty, which are characteristic of Judaism at its best. Its illustrations are drawn from the OT, and its style frequently recalls that of Proverbs, and the Prophets, particularly on its sterner side. The worldly are ‘adulteresses’ (4:4; cf. the OT conception of Israel as the bride of Jehovah, whether faithful or unfaithful), and the whole Epistle is full of warnings and denunciations; 54 imperatives have been counted in twice as many verses. The quotations, however, are mainly from the LXX; ‘greeting’ (1:1) is the LXX formula for the Heb. ‘peace,’ and occurs again in NT only in the letter of Ac 15:23. The points of contact with our Lord’s teaching have been already noticed; the Epistle follows Him also in its fondness for metaphors from nature (cf. the parables), and in the poetic element which appears continually; 1:17 is actually a hexameter, but it has not been recognized as a quotation. The style is vivid and abrupt, sometimes obscure, with a great variety of vocabulary; there are 70 words not found elsewhere in NT. There is no close connexion of ideas, or logical development of the subject; a word seems to suggest the following paragraph (e.g. ch. 1). Accordingly it is useless to attempt a summary of the Epistle. Its main purpose was to encourage endurance under persecution and oppression, together with consistency of life; and its leading ideas are the dangers of speech, of riches, of strife, and of worldliness, and the value of true faith, prayer, and wisdom. The Epistle is essentially ‘pragmatic’; i.e. it insists that the test of belief lies in ‘value for conduct.’ It does not, indeed, ignore the deeper side; it has its theology with its teaching about regeneration, faith, and prayer, but the writer’s main interest lies in ethics. The condition

of the heathen world around made it necessary to insist on the value of a consistent life. That was

Christianity; and neither doctrinal nor moral problems, as of the origin of evil, trouble him. The Epistle does not reach the heights of a St. Paul or a St. John, but it has its value. It presents, sharply and in emphasis, a side of Christianity which is always in danger of being forgotten, and the practical mind in particular will always feel the force of its practical message.

C. W. EMMET.

JAMES, PROTEVANGELIUM OF.—See GOSPELS [APOCRYPHAL], § 5.

JAMIN.—1. A son of Simeon (Gn 46:10, Ex 6:15, Nu 26:12, 1 Ch 4:24). The gentilic name Jaminites occurs in Nu 26:12. 2. A Judahite (1 Ch 2:27). 3. A priest (? or Levite) who took part in the promulgating of the Law (Neh 8:7; in 1 Es 9:48 Iadinus).

JAMLECH.—A Simeonite chief (1 Ch 4:34).

JAMNIA (1 Mac 4:15, 5:58, 10:69, 15:40, 2 Mac 12:8, 9, 40).—The later name of Jabneel (wh. see). The gentilic name Jamnites occurs in 2 Mac 12:9.

JANAI.—A Gadite chief (1 Ch 5:12).

JANGLING.—‘Jangling,’ says Chaucer in the Parson’s Tale, ‘is whan man speketh to moche before folk, and clappeth as a mille, and taketh no kepe what he seith.’ The word is used in 1 Ti 1:6 ‘vain jangling’ (RV ‘vain talking’); and in the heading of 1 Ti 6 ‘to avoid profane janglings,’ where it stands for ‘babblings’ in the text (1 Ti 6:20).

JANIM.—A town in the mountains of Hebron, near Beth-tappuah (Jos 15:53). The site is uncertain.

JANNAI.—An ancestor of Jesus (Lk 3:24).

JANNES AND JAMBRES.—In 2 Ti 3:8 these names are given as those of Moses’ opponents; the Egyptian magicians of Ex 7:11, 22 are doubtless referred to, though their names are not given in OT. They are traditional, and we find them in the Targumic literature ( which, however, is late). Both there and in 2 Ti 3:8 we find the various reading ‘Mambres’ ( or ‘Mamre’). ‘Jannes’ is probably a corruption of ‘Johannes’ (John); ‘Jambres’ is almost certainly derived from a Semitic root meaning ‘to oppose’ (imperfect tense), the participle of which would give ‘Mambres.’ The names were even known to the beathen. Pliny the Elder (A.D. 23–79) mentions ‘Moses, Jamnes (or Jannes), and Jotapes (or Lotapes)’ as Jewish magicians (Hist. Nat.

XXX. 1 ff.); thus ‘Jannes,’ at least, must have been a traditional name before the Christian era.

Apuleins (c. A.D. 130) in his Apology speaks of Moses and Jannes as magicians; the Pythagorean

Numenius (2nd cent. A.D.), according to Origen (c. Cels. iv. 51), related ‘the account respecting Moses and Jannes and Jambres,’ and Eusebius gives the words of Numenius (Prœp. Ev. ix. 8). In his Commentary on Mt 27:8 (known only in a Latin translation), Origen says that St. Paul is quoting from a book called ‘Jannes and Mambres’ (sic). But Theodoret (Com. in loc.) declares that he is merely using the unwritten teaching of the Jews. Jannes and Jambres are also referred to in the Apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus § 5 (4th or 5th cent. in its present form?), and in the Apostolic Constitutions, viii. 1 (c. A.D. 375). Later Jewish fancy ran wild on these names; according to some they were Balaam’s sons; according to others they were drowned in the Red Sea; or they were put to death, either for inciting Aaron to make the Golden Calf or at a later stage of the history.

A. J. MACLEAN.

JANOAH.—1. A town in the northern mountains of Naphtali, near Kedesh (2 K 15:29). It is probably the modern Yanūh. 2. A place on the border of Ephraim (Jos 16:6, 7); situated where the present Yānūn now stands, with the supposed tomb of Nun.

JAPHETH (Heb. Yepheth).—1. One of the sons of Noah. The meaning of the name is quite uncertain. In Gn 9:27 there is a play on the name—‘May God make wide (yapht) for Yepheth [i.e. make room for him], that he may dwell in the tents of Shem.’ The peoples connected with

Japheth (10:1–4) occupy the northern portion of the known world, and include the Madai

(Medes) on the E. of Assyria, Javan (Ionians, i.e. Greeks) on the W. coast and islands of Asia Minor, and Tarshish (Tartessus) on the W. coast of Spain. On the two traditions respecting the sons of Noah see HAM. 2. An unknown locality mentioned in Jth 2:25.

A. H. M’NEILE.

JAPHIA.—1. King of Lachish, defeated and slain by Joshua (Jos 10:3ff.). 2. One of David’s sons born at Jerusalem (2 S 5:14b–16, 1 Ch 3:5–8, 14:4–7). 3. A town on the south border of Zebulun (Jos 19:12); probably the modern Yāfā, near the foot of the Nazareth hills.

JAPHLET.—An Asherite family (1 Ch 7:32f.).

JAPHLETITES.—The name of an unidentified tribe mentioned in stating the boundaries of the children of Joseph (Jos 16:3).

JARAH.—A descendant of Saul, 1 Ch 9:42. In 8:36 he is called Jehoaddah.

JAREB.—It is not safe to pronounce dogmatically on the text and meaning of Hos 5:13 , 10:6. But our choice lies between two alternatives. If we adhere to the current text, we must regard Jareb (or Jarīb) as a sobriquet coined by Hosea to indicate the love of conflict which characterized the Assyrian king. Thus ‘King Jarib’ = ‘King Warrior,’ ‘King Striver,’ ‘King Combat,’ or the like; and the events referred to are those of B.C. 738 (see 2 K 15:19). Most of the ancient versions support this, as, e.g., LXX ‘King Jareim’; Symm. and Vulg. ‘King Avenger.’ If we divide the Hebrew consonants differently, We get ‘the great king,’ corresponding to the Assyr. sharru rabbu (cf. 2 K 18:19, 28, Is 36:4). It has even been thought that this signification may be accepted without any textual change. In any case linguistic and historical evidence is against the idea that Jareb is the proper name of an Assyrian or an Egyptian monarch. Other, less probable, emendations are ‘king of Arabia,’ ‘king of Jathrib or of Aribi’ (both in N. Arabia).

J. TAYLOR.

JARED.—The father of Enoch (Gn 5:15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 1 Ch 1:2, Lk 3:37).

JARHA.—An Egyptian slave who married the daughter of his master Sheshan (1 Ch 2:34f.).

JARIB.—1. The eponym of a Simeonite family (1 Ch 4:24 = Jachin of Gn 46:10, Ex 6:15 ,

Nu 26:12). 2. One of the ‘chief men’ who were sent by Ezra to Casiphia in search of Levites ( Ezr 8:16); called in 1 Es 8:44 Joribus. 3. A priest who had married a foreign wife (Ezr 10:18); called in 1 Es 9:19 Joribus.

JARIMOTH (1 Es 9:28) = Ezr 10:27 Jeremoth.

JARMUTH.—1. A royal city of the Canaanites (Jos 10:3 etc.), in the Shephēlab, assigned to Judah (Jos 15:35). It is probably identical with ‘Jermucha’ of the Onomasticon, 10 Roman miles from Elentheropolis, on the Jerusalem road. This is now Khirbet Yarmūk, between Wādy esSarūr and Wādy es-Sant, about 8 miles N. of Beit Jibrīn. 2. A city in Issachar, allotted to the

Gershonite Levites (Jos 21:29, LXX B Remmath). It corresponds to Ramoth in 1 Ch 6:73, and Remeth appears in Jos 19:21 among the cities of Issachar. Guthe suggests er-Rāmeh, about 11 miles S. W. of Jenīn, but this is uncertain.

W. EWING.

JAROAH.—A Gadite chief (1 Ch 5:14).

JASAELUS (1 Es 9:30) = Ezr 10:29 Sheal.

JASHAR, BOOK OF (sēpher ha-yāshār, ‘Book of the Righteous One’).—An ancient book of national songs, which most likely contained both religious and secular songs describing great events in the history of the nation. In the OT there are two quotations from this book—(a) Jos 10:12, 13; the original form must have been a poetical description of the battle of Gibeon, in which would have been included the old-world account of Jahweh casting down great stones from heaven upon Israel’s enemies. (b) 2 S 1:19–27; in this case the quotation is a much longer one, consisting of David’s lamentation over Saul and Jonathan. In each case the Book of Jashar is referred to as well known; one might expect, therefore, that other quotations from it would be found in the OT, and perhaps this is actually the case with, e.g., the Song of Deborah (Jg 5) and some other ancient pieces, which originally may have had a reference to their source in the title (e.g. 1 K 8:12f.).

W. O. E. OESTERLEY.

JASHEN.—The sons of Jashen are mentioned in the list of David’s heroes given in 2 S 23:32. In the parallel list (1 Ch 11:34) they appear as the sons of Hashem, who is further described as the Gizonite (wh. see).

JASHOBEAM.—One of David’s mighty men (1 Ch 11:11, 12:6, 27:2). There is reason to believe that his real name was Ishbosheth, i.e. Eshbaal (‘man of Baal’). Cf. ADINO and JOSHEBBASSHEBETH.

JASHUB.—1. Issachar’s fourth son (Nu 26:24, 1 Ch 7:1; called in Gn 46:13 Iob; patron. Jashubites (Nu 26:24). 2. A returned exile who married a foreigner (Ezr 10:29); called in 1 Es 9:30 Jasubus.

JASHUBI-LEHEM.—The eponym of a Judahite family (1 Ch 4:22). The text is manifestly corrupt.

JASON.—This Greek name was adopted by many Jews whose Hebrew designation was

Joshua (Jesus). 1. The son of Eleazar deputed to make a treaty with the Romans, and father of

Antipater who was later sent on a similar errand, unless two different persons are meant (1 Mac 8:17, 12:16, 14:22). 2. Jason of Cyrene, an author, of whose history 2 Mac. (see 2:23, 26) is an epitome (written after B.C. 160). 3. Joshua the high priest, who ousted his brother Onias III. from the office in B.C. 174 (2 Mac 4:7ff.), but was himself driven out three years later, and died among the Lacedæmonians at Sparta (2 Mac 5:9f.). 4. In Ac 17:6ff. a Jason was St. Paul’s host at Thessalonica, from whom the politarchs took bail for his good behaviour, thus (as it seems) preventing St. Paul’s return to Macedonia for a long time (see art. PAUL THE APOSTLE, § 8). The Jason who sends greetings from Corinth in Ro 16:21, a ‘kinsman’ of St. Paul (i.e. a Jew), is probably the same man.

A. J. MACLEAN.

JASPER.—See JEWELS AND PRECIOUS STONES, p. 467a.

JASUBUS (1 Es 9:30) = Ezr 10:29 Jashub.

JATHAN.—Son of Shemaiah ‘the great,’ and brother of Ananias the pretended father of Raphael (To 5:13).

JATHNIEL.—A Levitical family (1 Ch 26:2).

JATTIR.—A town of Judah in the southern mountains, a Levitical city (Jos 15:48, 21:14, 1 Ch 6:42). It was one of the cities to whose elders David sent of the spoil from Ziklag (1 S 30:27). Its site is the ruin ‘Attīr, N.E. of Beersheba, on a hill spur close to the southern desert.

JAVAN, the Heb. rendering of the Gr. Iaōn, ‘Ionian, is a general term in the Bible for Ionians or Greeks; very similar forms of the name occur in the Assyrian and Egyptian inscriptions. In the genealogical table in Gn (10:2, 4) and 1 Ch (1:5, 7) Javan is described as a son of Japheth and the father of Elishah, Tarshish, Kittim, and Dodanim (or better, Rodanim, i.e. Rhodes); from the reference to Kittim (Kition) as his son, it is possible that the passage refers particularly to Cyprus. In Is 66:19 Javan is included among the distant countries that will hear of Jahweh’s glory; in Jl 3:6 the sons of the Javanites are referred to as trading in Jewish captives with the Phœnicians and Philistines; in Ezk 27:13 Javan, with Tubal and Meshech, is described as trading with Tyre in slaves and vessels of brass. In all three passages the references are to the Ionian colonies on the coast of Asia Minor. In Ezk 27:19 Javan appears a second time among the nations that traded with Tyre; clearly the Ionians are not intended, and, unless the text is corrupt (as is very probable), the reference may be to an Arab tribe, or perhaps to a Greek colony in Arabia. In Dn 8:21, 10:20, 11:2, where ‘the king,’ ‘the prince,’ and ‘the kingdom’ of Javan are mentioned, the passages have reference to the Græco-Macedonian empire.

L. W. KING.

JAVELIN.—See ARMOUR, ARMS, § 1 (b).

JAZER.—An Amorite town N. of Heshbon, taken by Israel (Nu 21:32), allotted to Gad ( Jos

13:25 etc.), and fortified by it (Nu 32:35). It lay in a district rich in vines (Is 16:8 etc., Jer 48:32).

It is probably represented by Khirbet Sār, about 7 miles W. of ‘Ammān, a mile E. of Wādy Sīr.

Judas Maccabæus took the city, which was then in the hands of the Ammonites (1 Mac 5:9; Jos. Ant. XII. viii. 1).

W. EWING.

JAZIZ.—A Hagrite who was ‘over the flocks’ of king David (1 Ch 27:31).

JEALOUSY.—The law of the ‘jealousy ordeal’ (in which a wife suspected of unfaithfulness had to prove her innocence by drinking the water of bitterness [‘holy water’ mixed with dust from the floor of the Tabernacle]) is found in Nu 5:11–31. The conception of idolatry as adultery and of Jehovah as the Husband of Israel led the OT writers frequently to speak of Him as a jealous God (Ex 20:5, Dt 5:9, Jos 24:19, 1 K 14:22, Ps 78:58, Ezk 36:6, Nah 1:2). This jealousy is the indication of Jehovah’s desire to maintain the purity of the spiritual relation between Himself and His people. Extraordinary zeal for this same end is characteristic of the servants of Jehovah, and is sometimes called jealousy with them (2 Co 11:2, Nu 25:11, 13, 1 K 19:10). A few times the word is used in a bad sense (Ro 13:13, 1 Co 3:3, 2 Co 12:20, Gal 5:20, Ja 3:14 ,

16).

D. A. HAYES.

JEARIM, MOUNT.—Mentioned only in Jos 15:10, where it is identified with Chesalon (wh. see).

JEATHERAI.—An ancestor of Asaph (1 Ch 6:21); called in v. 41 Ethni.

JEBERECHIAH.—The father of Zechariah, a friend of Isaiah (Is 8:2).

JEBUS, JEBUSITES.—The former is a name given to Jerusalem by J in Jg 19:11 and imitated by the Chronicler (1 Ch 11:4); the latter is the tribe which inhabited Jerusalem from before the Israelitish conquest till the reign of David. It was formerly supposed that Jebus was the original name of Jerusalem, but the letters of Abdi-Khiba among the el-Amarna tablets prove that the city was called Jerusalem (Uru-salim) about B.C. 1400. No trace of Jebusites appears then. When they gained possession of it we do not know. J states that at the time of the Israelite conquest the king of Jerusalem was Adoni-zedek (Jos 10:3), and that the Israelites did not expel the Jebusites from the city (Jos 15:63, Jg 1:21). During the time of the Judges he tells us that it was in possession of the Jebusites (Jg 19:11), and gives a brief account of its capture by David (2 S 5:6–8). E mentions the Jebusites only once (Nu 13:29), and then only to say that, like the Hittite and Amorite, they inhabit the mountain. The favourite list of Palestinian nations which D and his followers insert so often usually ends with Jebusite, but adds nothing to their history. P mentions them once (Jos 15:8). They are mentioned in Neh 9:8 and Ezr 9:1 in lists based on D, while Zec 9:7 for archaic effect calls dwellers in Jerusalem ‘Jebusite’ (so Wellhausen, Nowack, and Marti). The name of the king, Adoni-zedek, would indicate that the Jebusites were Semitic,— probably related to the Canaanite tribes.

David captured their city and dwelt in it, and it was subsequently called the ‘city of David.’ From references to this (cf. JERUSALEM) it is clear that the Jebusite city was situated on the southern part of the eastern hill of present Jerusalem, and that that hill was called Zion. Its situation was supposed by the Jebusites to render the city impregnable (2 S 5:6).

One other Jebusite besides Adoni-zedek, namely, Araunah, is mentioned by name. The

Temple is said to have been erected on a threshing-floor purchased from him (cf. 2 S 24:16–24, 2 Ch 3:1). It would seem from this narrative that the Jebusites were not exterminated or expelled, but remained in Jerusalem, and were gradually absorbed by the Israelites.

GEORGE A. BARTON.

JECHILIAH (In 2 K 15:2 Jecoliah).—The mother of king Uzziah (2 Ch 26:3).

JECHONIAH.—See JEHOIACHIN.

JECHONIAS.—1. The Gr. form of the name of king Jeconiah, employed by the English translators in the books rendered from the Greek (Ad. Est 11:4, Bar 1:3, 9); called in Mt 1:11 f. Jechoniah. 2. 1 Es 8:92 = Ezr 10:2 Shecaniah.

JECOLIAH.—See JECHILIAH.

JECONIAH.—See JEHOIACHIN.

JECONIAS.—1. One of the captains over thousands in the time of Josiah (1 Es 1:9); called in 2 Ch 35:9 Conaniah. 2. See JEHOAHAZ, 2.

JEDAIAH.—1. A priestly family (1 Ch 9:10, 24:7, Ezr 2:36 [in 1 Es 5:24 Jeddu], Neh 7:39 , 11:10, 12:6, 7, 19, 21). 2. One of the exiles sent with gifts of gold and silver for the sanctuary at Jerusalem (Zec 6:10, 14). 3. A Simeonite chief (1 Ch 4:37). 4. One of those who repaired the wall of Jerusalem (Neh 3:10).

JEDDU (1 Es 5:24) = Ezr 2:36 Jedaiah.

JEDEUS (1 Es 9:30) = Ezr 10:29 Adaiah.

JEDIAEL.—1. The eponym of a Benjamite family (1 Ch 7:6, 10, 11). 2. One of David’s heroes (1 Ch 11:45), probably identical with the Manassite of 12:20. 3. The eponym of a family of Korahite porters (1 Ch 26:2).

JEDIDAH.—Mother of Josiah (2 K 22:1).

JEDIDIAH (‘beloved of J″’).—The name given to Solomon by the prophet Nathan (2 S 12:25) ‘for the LORD’S sake.’ See SOLOMON.

JEDUTHUN.—An unintelligible name having to do with the music or the musicians of the Temple. According to 1 Ch 25:1 etc., it was the name of one of the three musical guilds, and it appears in some passages to mask the name Ethan. Jeduthun (Jedithun) occurs in the headings of Pss 39, 62, 77, and appears to refer to an instrument or to a tune. But in our ignorance of Hebrew music it is impossible to do more than guess what Jeduthun really meant.

W. F. COBB.

JEELI (1 Es 5:33) = Ezr 2:56 Jaalah, Neh 7:58 Jaala.

JEELUS (1 Es 8:92) = Ezr 10:2 Jehiel.

JEGAR-SAHADUTHA (‘cairn of witness’).—The name said to have been given by Laban to the cairn erected on the occasion of the compact between him and Jacob (Gn 31:47).

JEHALLELEL.—1. A Judahite (1 Ch 4:16). 2. A Levite (2 Ch 29:12).

JEHDEIAH.—1. The eponym of a Levitical family (1 Ch 24:20). 2. An officer of David (1 Ch 27:30).

JEHEZKEL (‘God strengtheneth,’ the same name as Ezekiel).—A priest, the head of the twentieth course, 1 Ch 24:18.

JEHIAH.—The name of a Levitical family (1 Ch 15:24).

JEHIEL.—1. One of David’s chief musicians (1 Ch 15:18, 20, 16:5). 2. A chief of the Levites (1 Ch 23:8, 29:8). 3. One who was ‘with (= tutor of?) the king’s sons’ (1 Ch 27:32). 4. One of Jehoshaphat’s sons (2 Ch 21:2). 5. One of Hezekiah’s ‘overseers’ (2 Ch 31:13). 6. A ruler of the house of God in Josiah’s reign (2 Ch 35:8). 7. The father of Obadiah, a returned exile ( Ezr 8:9); called in 1 Es 8:35 Jezelus. 8. Father of Shecaniah (Ezr 10:2); called in 1 Es 8:92 Jeelus, perhaps identical with 9. One of those who had married foreign wives (Ezr 10:26); called in 1 Es 9:27 Jezrielus. 10. A priest of the sons of Harim who had married a foreign wife (Ezr 10:21) ; called in 1 Es 9:21 Hiereel.

JEHIELI.—A patronymic from Jehiel No. 2 (1 Ch 26:21, 22; cf. 23:8, 29:8).

JEHIZKIAH.—An Ephraimite who supported the prophet Oded in opposing the bringing of Judæan captives to Samaria (2 Ch 28:12 ff. ).

JEHOADDAH.—A descendant of Saul (1 Ch 8:36); called in 9:42 Jarah.

JEHOADDAN (2 Ch 25:1 and, as vocalized, 2 K 14:2. The consonants of the text in 2 K 14:2 give the form Jehoaddin [so RV]).—Mother of Amaziah king of Judah.

JEHOAHAZ

1. Jehoahaz of Israel (in 2 K 14:1 and 2 Ch 34:8, 36:2, 4 Joahaz) succeeded his father Jehu. Our records tell us nothing of him except the length of his reign, which is given as seventeen years (2 K 13:1), and the low estate of his kingdom, owing to the aggressions of Syria. A turn for the better seems to have come before his death, because the forces of Assyria pressing on the north of Damascus turned the attention of that country away from Israel (vv. 3–5).

2. Jehoahaz of Judah (in 1 Es 1:34 Joachaz or Jeconias; in v. 38 Zarakes) was the popular choice for the throne after the death of Josiah (2 K 23:30). But Pharaoh-necho, who had obtained possession of all Syria, regarded his coronation as an act of assumption, deposed him in favour of his brother Jehoiakim, and carried him away to Egypt, where he died (v. 34). Jeremiah, who calls him Shallum, finds his fate sadder than that of his father who fell in battle (Jer 22:10–12).

3. 2 Ch 21:17, 25:23 = Ahaziah, No. 2.

H. P. SMITH.

JEHOASH, in the shorter form JOASH, is the name of a king in each of the two lines, Israel and Judah.

1. Jehoash of Judah was the son of Ahaziah. When an infant his brothers and cousins were massacred, some of them by Jehu and some by Athaliah. After being kept in concealment until he was seven years old, he was crowned by the bodyguard under the active leadership of Jehoiada, the chief priest. In his earlier years he was under the influence of the man to whom he owed the throne, but later be manifested his independence. Besides an arrangement which he made with the priests about certain moneys which came into their hands, the record tells us only that an invasion of the Syrians compelled him to pay a heavy tribute. This was drawn from the Temple treasury. Jehoash was assassinated by some of his officers (2 K 11 f.).

2. Jehoash of Israel was the third king of the line of Jehu. The turn of the tide in the affairs of Israel came about the time of his accession. The way in which the Biblical author indicates this is characteristic. He tells us that when Elisha was about to die Jehoash came to visit him, and wept over him as a great power about to be lost to Israel. Elisha bade him take bow and arrows and shoot the arrow of victory towards Damascus, then to strike the ground with the arrows. The three blows which he struck represent the three victories obtained by Jehoash, and the blame expressed by Elisha indicates that his contemporaries thought the king slack in following up his advantage. Jehoash also obtained a signal victory over Judah in a war wantonly provoked, it would seem, by Amaziah, king of Judah (2 K 13:10 ff. ).

H. P. SMITH.

JEHOHANAN.—1. 1 Ch 26:3 a Korahite doorkeeper. 2. 2 Ch 17:15 one of Jehoshaphat’s five captains. 3. Ezr 10:6 (Jonas, 1 Es 9:1; Johanan, Neh 12:22, 23; Jonathan, Neh 12:11) high priest. He is called son of Eliashib in Ezr 10:6, Neh 12:23, but was probably his grandson, Joiada being his father (Neh 12:11, 22). 4. Ezr 10:28 (= Joannes, 1 Es 9:29), one of those who had taken ‘strange’ wives. 5. Neh 6:18 son of Tobiah the Ammonite. 6. Neh 12:13 a priest in the days of Joiakim. 7. Neh 12:42 a priest present at the dedication of the walls.

JEHOIACHIN, king of Judah, ascended the throne when Nebuchadrezzar was on the march to punish the rebellion of Jehoiakim. On the approach of the Chaldæan army, the young king surrendered and was carried away to Babylon (2 K 24:8ff.). His reign had lasted only three months, but his confinement in Babylon extended until the death of Nebuchadrezzar—thirtyseven years. Ezekiel, who seems to have regarded him as the rightful king of Judah even in captivity, pronounced a dirge over him (19:1ff.). At the accession of Evil-merodach he was freed from durance, and received a daily allowance from the palace (2 K 25:27f.). Jeremiah gives his name in 24:1, 27:20, 28:4, 29:2 as Jeconiah, and in 22:24, 28, 37:1 as Coniah. In 1 Es 1:43 he is called Joakim, in Bar 1:3, 9 Jechonias, and in Mt 1:11, 12 Jechoniah.

H. P. SMITH.

JEHOIADA.—1. Father of Benaiah, the successor of Joab, 2 S 8:18, 20:23 etc. It is probably the same man that is referred to in 1 Ch 12:27, 27:34, where we should probably read ‘Benaiah the son of Jehoiada.’ 2. The chief priest of the Temple at the time of Ahaziah’s death (2

K 11:4 etc.). The Book of Chronicles makes him the husband of the princess Jehosheba ( or Jehoshabeath, 2 Ch 22:11), by whose presence of mind the infant prince Jehoash escaped the massacre by which Athaliah secured the throne for herself. Jehoiada must have been privy to the concealment of the prince, and it was he who arranged the coup d’état which placed the rightful heir on the throne. In this he may have been moved by a desire to save Judah from vassalage to Israel, as much as by zeal for the legitimate worship.

H. P. SMITH.